Times New Roman. Arial. Courier New. These are the default fonts of our computer-driven world, the ordinary styles from which we stray only when we need that ‘wow’ factor. But these familiar fonts—and every other font—are actually the products of an art form that’s over 2,000 years old.

It’s commonly known that before technological advances like the printing press, all letters and manuscripts were written and copied by hand. When alphabets were first developed, very few people knew how to read or write them. “For a thousand years, writing was in the hands of specialists who raised the craft of calligraphy to the level of fine art,” Margaret Shepherd explained in her book Learn Calligraphy: The Complete Book of Lettering and Design. It was the emphasis on the decorative aspects of writing that elevated calligraphy to an art form.

Many of the scribes who practiced calligraphy were tasked with preserving and glorifying the word of God. Their art was greatly influenced by the architecture, textiles and stained glass that surrounded them, and they worked to present the text in beautiful ways, devoting considerable time and effort to their craft. But the Renaissance brought about typesetting, which, while increasing public literacy, significantly reduced the need for these scribes’ unique skill set. During this time, says author Ralph Cleminson, the scribe became the calligrapher.

The Industrial Revolution marked a low point for the craft, “when manufactured books, textiles and housewares drove handmade things out of fashion,” wrote Shepherd. But calligraphy was revived with the Arts and Crafts Movement that developed in England in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Not only did the art of writing regain its popularity, but techniques for making pens, inks and parchment were revisited as well.

In the 1970s, calligraphy grew in popularity among American hobbyists, as pens and other supplies grew more affordable. “In the present day, the fact that most written texts are not handwritten has redirected our attention to the aesthetic aspects of writing,” wrote Cleminson. “To choose to write something by hand is to choose to create a particular visual impact, and more and more people are developing an interest in calligraphy and an appreciation of its potential.” The Varied Hands

The Varied Hands

The first forms of writing developed independently of each other throughout the ancient world and spread as peoples took up existing scripts or altered them to create their own. These different scripts, or styles, are referred to by calligraphers as hands.

Pat Tetidrick, a local calligrapher and teacher of the art, focuses on five hands: Bookhand, which dates back to the reign of King Charlemagne during the first century; the Celtic, or Uncial, hand, developed in the fifth or sixth century; the Italic style, developed in Italy during the 15th century; Gothic, or Black Letter, a medieval hand from the 15th century commonly identified with the type produced by Gutenberg’s printing press; and Copperplate, developed during the 18th century. These are just a tiny fraction of the hands used by calligraphers today.

Cleminson explains that the evolution of the writing instruments used by scribes and calligraphers also played a major role in the development of the various hands. The use of brushes by Chinese and Japanese calligraphers, for example, influenced the “bold, sweeping strokes of the characters that make up their writing systems.”

Today, as texts and emails have become the predominant means of delivering messages, the act of putting pen to paper has become increasingly rare. But those who see the beauty of writing and embellishing messages by hand have continued to keep the art of calligraphy alive. One of these individuals is Pat Tetidrick. Once a student of calligraphy herself, Tetidrick was ushered into teaching when her instructor couldn’t make it to the last session of their class and asked her to fill in. She has since gone on to teach classes at Lakeview Museum and for the Peoria Park District and Illinois Central College’s Adult Community Programs.

Although challenged when she first began studying the art, Tetidrick stuck with it because she saw the great potential of adding visual appeal to the written word. “My first teacher made it so interesting and artistic that I read and experimented with different hands,” she said. And one of Tetidrick’s students felt the same way about her. Years ago, when she was planning her wedding, Lisa Mack wanted her invitations to stand out from the rest of the mail, and so, she signed up for one of Tetidrick’s classes through the Park District. This is one of the most common reasons that people become interested in calligraphy.

In the class, Tetidrick focused on the Italic hand, the one that most calligraphy students learn first. A simple, yet elegant script, it is ideal for addressing wedding invitations and writing poems, scripture verses and more. Eight years later, it would become the primary hand that Mack would employ in her own business, Calligraphy by Lisa.

Both women believe that calligraphy adds something very special to words on a page. Tetidrick loves a bride’s excitement when she picks up her wedding invitations—proof that her art is appreciated. She also takes pleasure in the simple enjoyment on someone’s face when she prints their name by hand in several different styles: “Their name becomes special.” I can attest to that, as I very much enjoyed watching Tetidrick write my own name in five different hands. It was amazing to watch the lines grow thinner and thicker as she applied varying amounts of pressure and made different strokes with the pen.  Tools of the Trade

Tools of the Trade

After choosing which hand to use for a particular piece of work, calligraphers pick the pen that will give them the best effect. In the early days, quills, handmade pens and brushes were prevalent, and while some calligraphers still use these tools, most now use felt-tipped markers or

metal pens.

Different hands call for different types of pens. Some use ink cartridges; others are dipped in bottled ink. And each hand calls for the pen to be held in different positions and at different angles. Mastering the nuances of any given style can take years of practice, noted Tetidrick, who didn’t start teaching Copperplate until she had perfected it herself, which took about five years.

The choice of paper is also important. Early calligraphers wrote on parchment and papyrus, which are still in limited use today, but machine-made paper is much more widespread and affordable. The possibilities seem endless, as paper comes in all sizes, textures and colors.

Just as painters sketch out their designs before picking up their brushes, calligraphers plan everything out with pencil before reaching for their pens. Tetidrick begins by writing her message on a piece of paper, and then measuring each line so she knows precisely where to place it on the final page. Knowing the length of each line ensures that she can center everything correctly or lay it out around whatever graphics she may wish to include.

Mack notes that a light box is an indispensible tool for calligraphers; anyone who is serious about calligraphy needs to have one, adds Tetidrick. Made of wood with a glass top that sits above a light bulb, Mack’s light box was built by her father when she did indeed “get serious,” and she still uses it today. She starts by drawing lines on the glass that closely resemble the writing paper used by young children, adjusting the space between the lines as needed, depending on the size of the letters she’s working with. The paper is then placed on top of the glass, the lines projecting through the page and helping to keep her writing straight without leaving marks on the final project. After the calligraphy is done in ink, the piece can be enhanced with embossments, graphics or photos.

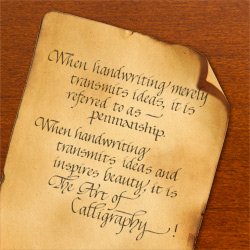

One of Tetidrick’s favorite sayings goes, “When handwriting merely transmits ideas, it is penmanship. When handwriting transmits ideas and inspires beauty, it is the art of calligraphy.” Most often, the words you see on a page have been put there by laser-jet printers that stamp out copy after copy at dizzying speeds. Although necessary for the economical mass distribution of printed materials, technology has taken us far from the old-world beauty and grandeur of hand lettering.

Yet Tetidrick and Mack are quite sure that their art will not soon fade away. Calligraphy demonstrates the devotion of time, great care and artful craft. It is intimate, personalized, memorable and effective. As Mack says, there’s nothing quite like the handwritten word. a&s

All calligraphy shown was done by Pat Tetidrick, who can be reached at ijb856@comcast.net or 676-5513.

- Log in to post comments