Our ongoing quest to connect local readers to the work of authors with central Illinois ties takes us this month to Portland, Maine, current home of Kathryn Miles, a 1992 Metamora High School graduate who grew up in the Lake Santa Fe subdivision near Germantown Hills.

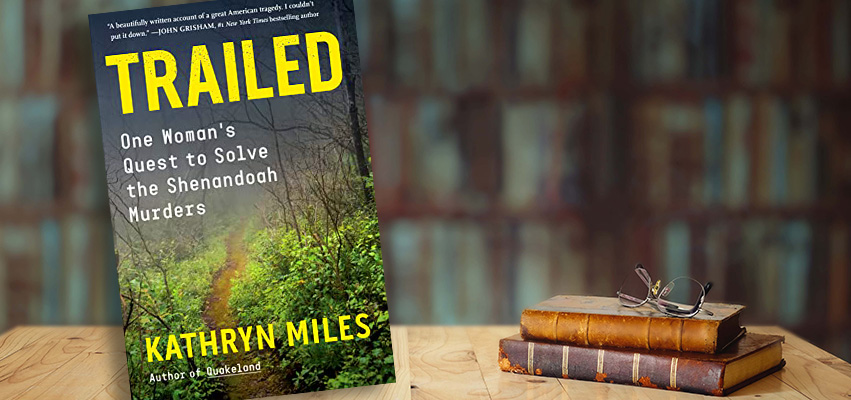

Miles has been a long-form journalist, author and university professor since leaving her hometown for St. Louis University three decades ago. Her fifth book, Trailed: One Woman’s Quest to Solve the Shenandoah Murders, published by Algonquin Books, is to be released on May 3.

Peoria Magazine (PM): Hi Kate. Tell us what Trailed your latest book, is all about.

Kathryn Miles (KM): In May 1996, Julie Williams and Lollie Winans were brutally murdered while backpacking in Virginia’s Shenandoah National Park, adjacent to the world-famous Appalachian Trail.

The young women were skilled backcountry leaders and they had met — and fallen in love — the previous summer while working at an outdoor program for women. Despite an extensive joint investigation by the FBI, Virginia police and National Park Service experts, the case remained unsolved.

In early 2002, in response to mounting political pressure, then-Attorney General John Ashcroft announced that he would seek the death penalty against Darrell David Rice — already in prison for assaulting another woman — in the first capital case tried under new, post- 9/11 federal hate crime legislation. Two years later, the Department of Justice quietly suspended its case against Rice, and the investigation grew cold.

In 2002, I was a newly minted professor at Unity College, the school Lollie was attending when she was murdered. The indictment rocked our small community. In subsequent years, I became the trail correspondent for Outside Magazine. Lollie and Julie’s story had always remained in my mind. On the 20th anniversary of their murders, I proposed a long-form feature story about the crime to my editor. I thought the piece would be a fairly straightforward account of the crime and the FBI’s attempts to solve it. It turned out to be anything but.

PM: What was it about Julie Williams and Lollie Winans that so motivated you to tell their story?

KM: I was sexually assaulted when I was 16 years old and really struggled with how to make sense of that experience. It wasn’t until I was in college and discovered backpacking that I really felt like I found a way to feel strong and powerful in my own body. Backpacking was a kind of salvation for me. When I learned that two young women my age had been murdered camping off a national park trail, it really shattered my sense of safety in the wilderness.

At the time of their murder, the Internet was still nascent. I started doing research and was shocked to learn how many others – particularly women and people who identify as LGBTQ+ — had been murdered while hiking on some of our country’s most popular trails. That awareness profoundly changed my own relationship with the natural world.

I resisted the idea of writing this book for quite a while. With the feature story, I knew I could skirt around the edges of what was most disturbing and painful … I’d seen how great a toll writing these kinds of books has taken on other authors, and I didn’t think I had the fortitude to go down such dark holes. But the more I began to understand just how solvable this case remains — and just how many individuals have been affected by it — the more I realized it would be selfish not to pursue the project.

PM: What did you find in your investigation that the FBI, Virginia police and National Park Service authorities did not, or at least did not act upon?

KM: A good part of the book is my attempt to recreate the amazing lives of Lollie and Julie and the great love they had for one another. But the main thread is the answer to that question. There were multiple missteps that ultimately prevented a conviction.

I should say that many talented and dedicated law enforcement officials worked tirelessly on this case (and were a tremendous help in writing the book). That said, it is true that a lack of understanding of wilderness crimes, the culture of the hiking community, and most notably, real bias on the part of key investigators led to a wholly botched case.

What is most disturbing is just how often this happens. Since 1980, over 2,600 people have been exonerated after being wrongly convicted of capital crimes. The overwhelming majority were the result of bias on the part of investigators and prosecutors. Couple that with the fact that there are currently over 250,000 cold murder cases in the U.S., and you begin to get a glimpse of just how big a crisis we have with our justice system.

PM: You believe the man the police originally arrested for the crime was the wrong guy, correct? At the risk of declaring a spoiler alert, do we dare ask whodunnit?

KM: I do. No evidence has ever been found linking Darrell David Rice to the crime, despite a lengthy investigation that included planting one of the FBI’s leading undercover agents in Rice’s cell and spending millions of taxpayer dollars.

As part of my research, I partnered with the University of Virginia’s Innocence Project. Their director, noted attorney Deirdre Enright, has always said the only real way to prove someone’s innocence is to establish someone else’s guilt. We reinvestigated the case using all of the evidence obtained by officials and pursued multiple other leads. In the book, I make a case for what I believe is the strongest and most likely of these alternative suspects.

PM: To what other conclusions did your research and writing bring you?

KM: I think we all want certainty, particularly when something terrible happens … We want to believe that justice will prevail and that the perpetrator will be caught and punished. And in the era of crime dramas like CSI, we all want to believe that forensic science will lead us to that certainty. But that rarely, if ever, is the case. Forensic science is a highly subjective, fallible field of inquiry that historically has not been subjected to the same scientific rigor of other disciplines. Particularly given the rise of cases solved with trace DNA and genealogical profiling, we must invest in better, more rigorous science while also preserving more traditional methods of investigation.

I also learned a lot about access to wilderness and nature. Too many people still don’t feel welcome or safe there, whether it’s because of the color of their skin, the shape of their bodies, their sexual and religious orientation, or their past experiences. As a nation, we have a long way to go to create truly equal access to our most beautiful places.

PM: You started down this path in 2016, so this book has been six years in the making. What was it about this one that posed such a challenge?

KM: This book was definitely the most involved and lengthy process of any book I’ve written. I think that’s true for several reasons. First, the learning curve for the really heady science, like DNA analysis, was a steep one. Secondly, because of the gravity of the subject matter, it was really important to me that I get everything absolutely right … Finally, because so much of the research was so grim, I had to set very strict boundaries with myself just to make sure I could sleep at night. One rule I made was to never work on the project after dark, which made for short days during the winters here in Maine!

PM: I see that you got best-selling author John Grisham to comment on Trailed, which is quite the catch. How’d you manage that?

KM: John has been a huge and selfless supporter of both the UVA Innocence Project and their new Justice Center. A mutual friend introduced us when she learned we were both working on books about a serial killer in Virginia. I’ve been so grateful for his encouragement.

PM: Trailed won’t be released until May, but you’ve already sold the film rights to it. Tell us about that.

KM: I’m currently working with a production company (Muse Entertainment) to develop a limited-run streaming series about the crime and investigation. It’s been very gratifying to work in a new medium and to learn how to adapt the written word for the screen.

PM: This is your fifth full-length book. Tell us briefly about the others, and if there’s a common theme among them in terms of the subjects you like to tackle.

KM: If there’s something that unites all of my work, it’s my interest in the relationships we form with both the built and natural environment and how we develop a sense of place there. My first book, Adventures with Ari, was a combination of memoir and backyard naturalism and details a year my dog and I spent in the wilderness around my house. I’ve written about the Irish famine and subsequent pandemic, Superstorm Sandy and, most recently, earthquakes and disaster preparedness in Quakeland: On the Road to America’s Next Devastating Earthquake. I love any excuse to explore the intersection of science and narrative and how we make sense of the world in which we live.

PM: Is there a fiction book in your future?

KM: I’ve kicked around a few ideas for a novel, including one actually set in Peoria during the 1940s — the height of the Shelton Gang’s reign there — but for now I’m far too entranced by all the fascinating true stories yet to tell.

PM: The theme for this issue of Peoria Magazine is Innovation. I’m curious about your approach, how you go about your craft.

KM: I think my job is primarily about being a good listener. It’s about finding the actual innovators and sitting at their knee for a day or a week so that I can understand their world. Sometimes that means going down into a silver mine or up in a Coast Guard rescue helicopter; other times it’s spending hours in a seismology lab or a night on patrol with a ranger or game warden. They’re the experts and visionaries; my job is just to bring their stories to readers in an entertaining and comprehensive way.

PM: Maine is home for you now, but I should mention that we go way back, that we first met when you were a teenager working part-time at the Journal Star, that you were raised in the Metamora area. How did your experience growing up in central Illinois shape you as a person and as an author?

KM: Both sides of my family have long roots in central Illinois (my parents were high school sweethearts at Richwoods High School). My commitment to environmental issues was born out of growing up in the Midwest and seeing the impact of industrial agriculture on both the landscape and human health (Pekin native Sandra Steingraber’s book about her experience with environmentally induced cancer in her book, Living Downstream, was a formative text for me).

Working at the Journal Star as a high school student was a dream come true for a precocious teenager who wanted to save the world. I was enraptured by the bustling newsroom and the beat reporters who went after stories day after day. That experience engrained in me the idea of the fourth estate and both the power and responsibility journalists have.

No matter how long I live in the land of Yankee reserve, I will always maintain my sense of Midwesterner hospitality. Give me even the slightest excuse, and I will show up at your house with a casserole, some freshly baked banana bread, or a dozen snickerdoodles — and maybe all three.

Mike Bailey is editor in chief of Peoria Magazine