At the time it was originally constructed, Woodruff Boulevard—or Woodruff Parkway, as it was sometimes referred to—was considered to be a government-financed boondoggle. That was certainly the case for the author of an article written in 1940 for the Peoria Journal Transcript which declared: “Dry Run Creek Project Is Completed At Cost of $570,000, WHY?”

That price tag of $570,000 is no small amount today, equating to approximately $10.9 million when adjusted for inflation. Most who read about this boulevard today will either have never heard of it or have forgotten that it existed. When completed in 1940, it ran from Nebraska Avenue to University Street along Dry Run Creek. Until just a few years ago, a portion of Woodruff Boulevard was still intact between Nebraska Avenue and Sheridan Road. That portion was removed with the enlargement of the Peoria High School athletic facilities in 2015.

A Leisurely Connection

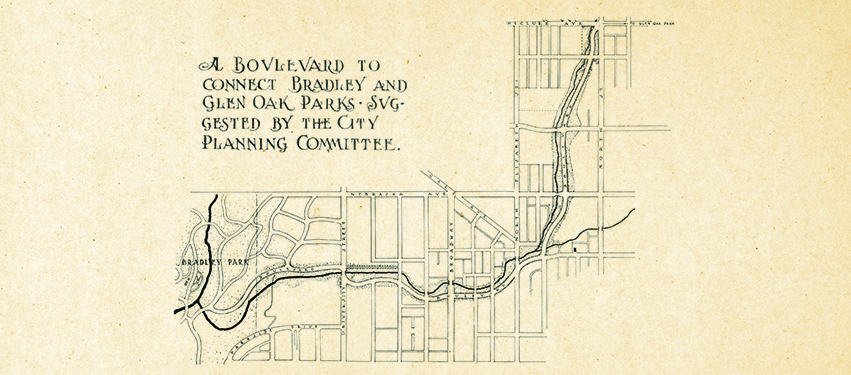

A boulevard along Dry Run Creek was proposed as early as the first decade of the 20th century. It was envisioned as a way to not only improve the creek itself, but as a means to connect some of Peoria’s parks. Most notably, it would have connected Bradley Park to Glen Oak Park, while including other smaller parks and recreational facilities as part of its design.

When the plans for Woodruff Boulevard were originally conceived, the world had a more laidback pace. The idea of a leisurely drive by horse-drawn buggy or carriage, in what then would have been a somewhat rural part of Peoria, was appealing. By the time a portion of the boulevard was finally constructed in 1940, however, the automobile had become commonplace—and a road that wound inefficiently through the city was a luxury, especially with the United States in the midst of a depression.

Ironically, it was the Great Depression which finally made the completion of the first portion of Woodruff Boulevard possible through the auspices of the Works Projects Administration. The WPA was a federal relief organization created as part of Franklin Roosevelt’s “New Deal” to put Americans back to work and improve public infrastructure. The construction of the boulevard also included improvements to Dry Run Creek itself, which, based on accounts and photographs of the time, was unappealing and unsanitary. The valley where it flowed was a dumping ground for rubbish, so plans to improve the meandering creek were not without merit.

The project faced several stumbling blocks, according to the 1940 article. Part of the plan for creek improvements called for the placement of interlocking concrete panels to line the creek basin. Several times, flash floods disturbed these panels or washed out incomplete areas, necessitating reconstruction and fill dirt to be brought in for re-grading purposes. In addition, as the economy improved in the late 1930s, many WPA workers found more gainful employment.

Moreover, what appeared to be a bad design element caused problems with the completed portions of the Dry Run Creek improvements. The finished design incorporated a sanitary sewer beneath the creek bed, with manhole covers that were flush with the concrete panels. As such, the 1940 article posed the following question: “How a workman can enter the sewer when the creek is full of water remains a question, and it would seem that when a break in the sewer occurs, its repair will become a major engineering problem.” Nevertheless, the author wrapped up his criticisms by declaring, “The area that was once an eyesore has been cleaned up, although it certainly has not been transformed into the wonderland of the original dream.”

Consumed By the Interstate

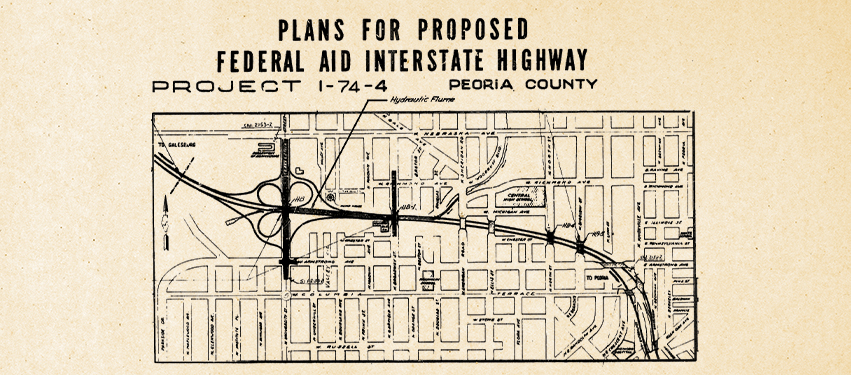

Wonderland or not, the Woodruff Boulevard of 1940 would last barely more than a decade before its fate was sealed by another government project—one that would dwarf the original work in terms of cost and scale. That project was the construction of Interstate 74 through Peoria. Originally envisioned as a crosstown highway connecting downtown Peoria with Tazewell County, the roadway soon became part of the much larger interstate highway system. This change in plans meant that the interstate would move through downtown Peoria west toward Galesburg.

There was much debate about where to locate the highway in relation to the downtown area, but once that was settled, its western terminus put it right at the doorstep of Woodruff Boulevard. Because there was already a natural valley at Dry Run Creek, the decision on which direction Interstate 74 should take as it left downtown was an easy one. Of course, that meant most of the relatively new Woodruff Boulevard and the earlier creek improvements would be eliminated. It also meant that the dream of connecting Peoria’s parks via boulevard would die with the interstate. The four-lane winding roads and improvements to Dry Run Creek would instead give way to a multilane superhighway and a modern flume drainage system to channel all of the water.

I personally investigated the remains of the original Dry Run Creek improvements near Sheridan Road, which tie into the more modern flume system of the early 1960s. The flumes that sit between the westbound and eastbound lanes of I-74 are open to the air in some sections and visible as you drive down the interstate.

The flumes are impressive, as are the more recent interstate improvements from the early 21st century, which were made approximately 45 years after the original interstate’s construction. One can see the seams where workers connected the newer, upper portion of the flume channel to the one from the early 1960s. The flumes are the same width but appear to be taller than when first built. As you travel along I-74 past Peoria High School to the University Street overpass, you are essentially following the original route of Woodruff Boulevard.

The Vision Renewed

While the idea of a scenic greenway winding its way through Peoria was progressive for the early 20th century, it appears to have become obsolete in the minds of many by the 1930s. One imagines that if the author of the 1940 article saw what had become of what he assessed to be a government boondoggle, he might be impressed that a road to nowhere had become a road to the future and beyond, in the form of the interstate highway and drainage improvements. There may, however, be a means to have both the interstate and a greenway, in at least a portion of Peoria.

Over the last couple months, a proposal has been put forward from visionary philanthropist Kim Blickenstaff that would accomplish both goals. According to Blickenstaff’s KDB Group, “The park would be suspended over 4.5 blocks of Interstate 74—between Adams Street and Perry Avenue—and contain recreational paths, children’s play areas, entertainment platforms, expression areas for the arts, gardens, water features and a several distinctive architectural elements. It could be at once a cultural hub and a contemplative retreat.”

In this post-COVID environment, citizens are embracing leisure and the outdoors once again. If the original vision of Woodruff Boulevard had survived to this day, it might be experiencing a renaissance right now. With the most recent proposal on the drawing board, there may yet be an opportunity to fulfill the vision of progressive Peorians from times past. PM

Chris Farris is reference assistant librarian at the Peoria Public Library Local History and Genealogy Department.

- Log in to post comments