Autonomous technology is not just changing the way we drive—it’s rebooting our entire transportation system.

It’s not just the adaptive cruise control or automatic lane keeping. It isn’t the collision-mitigation braking system or blind spot monitoring; it’s not the steering assist or night view assist. But taken together, something about the collective impact of these technologies tugs at our human heartstrings. Facing the fully “driverless” car, we waver.

The story is nothing new. A technology develops, a once-far-off future draws nigh, and change arrives. Society grapples with itself, and life goes on, usually for the better. It’s the way of the phone, once feared that it would quicken life to an unbearable pace; the home computer, surely practical only to the niche user; and the Internet, targeted for “catastrophic collapse” in the mid-1990s. Even the automobile was deemed a mere fad: “The horse is here to stay,” warned one Michigan banker in 1903, dismissing Henry Ford’s machine as novelty.

Today, it’s not just the horse that’s disappeared. With test vehicles from the likes of Daimler, BMW, Volkswagen, Audi and Google racking up on-road mileage without human intervention, the driver is now missing as well. The self-driving car is here, and it seems we’ve entered the grappling stage.

“Every innovative automaker and tier-one supplier is heading towards autonomous driving,” declares Bobby Hambrick, founder of AutonomouStuff, the world’s leading single-source supplier of autonomous components and services. “They’re all in a race right now.” By the year 2030, predicts Boston-based firm Lux Research, Inc., self-driving cars will create $87 billion in opportunities for automakers and technology developers, even as other industries fall by the wayside.

“In the past, the sensing technologies haven’t been where they needed to be,” Hambrick notes. “A lot has changed in the last few years.” With radically-improved technologies for autonomous driving and the cost of components in freefall, the automotive market is primed for mass adoption. “We’re right on that edge right now.”

In fact, many of these features are on the road today—and quite likely in your own garage. “Your car can already automatically follow a car in front of you, automatically brake, keep you in a lane…” Hambrick muses. The autonomous future is here already. So the question becomes: not can we turn over the wheel… but should we?

A Global Brand

Bobby Hambrick is the epitome of a go-getter. He’s a fast talker—highly-technical industry jargon rolls like butter off his tongue until layman’s terms are requested. Ask for his ten-year goals and he’ll hesitate, before rattling off a lengthy list he knows he’ll have completed in closer to two. Considering his energy and enthusiasm, his lifelong affinity for robotics, and his past experience designing and programming automated controls for industrial facilities, the central Illinois native’s early success with AutonomouStuff is no real surprise. Hambrick founded the Morton, Illinois-based company in early 2010, having thoroughly researched the emerging field of autonomous systems—and it’s been growing ever since.

“The government was throwing out a lot of really big—$100 million—contracts to develop radar technology,” he recalls. “I noticed guys in the mining industry… were trying to repurpose industrial-type sensors for the ‘eyes’ of vehicles. But I didn’t see why no one was utilizing automotive technology for this, because automotive companies were making technologies for other applications that could be repurposed.”

Spying a gap in the supply chain, Hambrick began securing global partnerships with automotive and other high-tech suppliers to gain access to their sensor technologies for markets they would typically consider “non-traditional.” In five short years, AutonomouStuff has accumulated more than 1,000 customers around the world, including automotive, mining and agricultural OEMs; tier-one suppliers; universities; aerospace clients; and “just about every major military contractor throughout North America.” But as a bootstrapped enterprise, it wasn’t easy. With no external funding or investment, Hambrick calls the company’s start “challenging at first”—an old-school launch to a novel business.

“I did everything I could via remotes—connecting through email, reading articles in magazines and trade publications,” he explains. “I’d find names and contact them directly and [through] social media… but mostly it was just digging… and contacting people who were interested in the technologies. It was a lot of homework in the beginning, getting connected.”

As recognition of the AutonomouStuff brand took hold, people started coming to him. “The getting-connected part is a whole lot easier now,” he notes. “Any university, researcher or roboticist doing research in this area is probably a customer of ours.”

Today, the company dominates its niche as a global supplier of technology products related to autonomous driving, automatic guided vehicles (AGVs), unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), obstacle detection, collision avoidance, intersection safety and mapping, and technical support services. Hambrick calls it “technology scouting”—pulling together the best technologies from large companies and startups alike, and providing clients instant access to the market.

“We sell the components that enable autonomy,” he says. “We already have the customer base, so if there’s some new tech that somebody wants to try out, we’re a great avenue... We’re constantly getting approached by people that have new ideas and new technologies.”

Your Car on Android

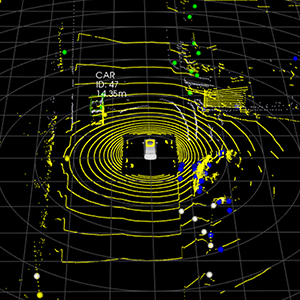

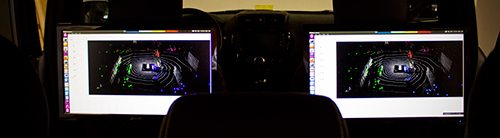

The company’s flagship product is PolySync—the world’s first operating system for autonomous vehicles. It’s a plug-and-play platform of software tools and services that makes hardware components such as LiDAR, radar, cameras and GPS more accessible to developers, allowing them to design, build and test their own modular components without having to write the software from the ground up. It frees them to focus their time and energies on building specialized apps, which can be deployed on any PolySync-enabled vehicle.

The software’s success sparked the creation of Harbrick, a spinoff startup that blends the names of its two cofounders, Hambrick and Josh Hartung. The former head of hardware for Kogeto, a consumer electronics firm focused on panoramic video and web services, Hartung is based in northern Idaho, where the new company will be headquartered. While the focus of AutonomouStuff remains broad, Harbrick will specialize in software development for autonomy systems—namely, PolySync.

At AutonomouStuff’s Morton facility, two demonstration cars run on the software, which Hambrick likens to Android for a smartphone. “Android is an operating system that’s independent of the hardware,” he explains. “Why don’t phone manufacturers make their own operating systems? Because it doesn’t really make sense [when] they can just take advantage of something that’s proven to work… and avoid reinventing the wheel.”

That model was critical in the tremendous growth of the smartphone industry because it enabled a sprawling network of app developers to simply build on top of an existing system. “Now you can download billions of apps, and none of those app developers care what’s going on in the operating system,” says Hambrick. “So, what we do is essentially Android for a car.”

PolySync relies on 15 different systems to collect sensory data, and takes care of what Hambrick calls “all the non-sexy stuff”: time synchronization, data management and the like. With these complexities handled behind the scenes, the interface brings all the data together in one place. “We put [the data] on top of this 3D viewer so developers can instantly—within 13 minutes of… installing the operating system—be 80 percent of the way towards their application,” he explains. “The operating system makes sure everything is functionally safe [and] all the data is good… It makes it much easier and quicker to lower the barrier to get to autonomous driving.”

Naturally, applications like adaptive cruise control and automatic lane-keeping are easily marketed, as they eliminate some of the hassles of driving. But they can also minimize crashes—the real selling point of the system, Hambrick suggests.

Adapt or Perish

About 1.3 million people die each year in car-related deaths around the world. That’s more than one 9/11 attack every 24 hours, or three times the number of U.S. casualties during World War II, notes Guy Fraker, cofounder and CEO of get2kno, Inc. and chief learning officer at AutonomouStuff. He says autonomous technology is capable of preventing 80 to 95 percent of those deaths.

“If there was a disease that was a leading killer of young adults around the world… and a vaccine was developed to prevent 95 percent of those fatalities, and the government and drug manufacturers did not go to market because it only prevented 95 percent of fatalities, how would people react?” Fraker asks. And yet, that’s exactly the rationale some have used to discourage autonomous vehicles.

“We hold the machine to a higher standard because it’s not us,” he adds, noting the self-driving car can never be 100-percent reliable in eliminating accidents. “But human error is the direct cause of 93 percent of all accidents,” he stresses—and those deaths can be prevented.

One growing segment of AutonomouStuff’s business model lies in consulting, advising clients of the impact of autonomous technology on their industries. As chief learning officer, Fraker puts his 25 years of experience in the auto insurance industry to work, with a focus on the pivotal junction where emerging technologies intersect with current business models. “My role is to help traditional business get comfortable with technologies that could disrupt their whole way of being.”

“Just think,” Hambrick muses, “If cars aren’t crashing anymore… that affects a lot of industries.”

Among them? “First responders and healthcare,” Fraker begins. “Fifty percent of all emergency room occupancies are car-crash related. And certainly [the] legal [industry]... cellular, telecom, disability insurance… all the way to mining.” With dramatically fewer traffic accidents, the mitigation of stop-and-go congestion could cure range anxiety—the fear that a vehicle has insufficient power to reach its destination—which has kept consumers from buying electric cars. “It becomes a watershed for electric vehicles, which impacts mining,” he adds, pausing for a quick breath, “with all the minerals needed for electric cars and batteries.”

Thinking through this multilayered cycle of chain reactions is enough to make your head spin. It’s easy to see why AutonomouStuff is prioritizing its consulting services.

“There’s a really big ‘crash economy’ [supported by] vehicle accidents,” Hambrick says. The company’s consultants help clients who are dependent on that economy to construct new business scenarios. According to Investopedia contributor Joseph Dallegro, hundreds of billions of dollars will be lost by car-related enterprises that don’t adjust fast enough to autonomous tech. But there’s more.

“Think of the lost revenue for governments via licensing fees, taxes and tolls, and by personal injury lawyers and health insurers,” he writes. “Who needs a car made with heavier-gauge steel and eight airbags—not to mention a body shop—if accidents are so rare? Who needs a parking spot close to work if your car can drive you there, park itself miles away, only to pick you up later? Who needs to buy a flight from Boston to Cleveland when you can leave in the evening, sleep much of the way, and arrive in the morning?”

Companies must adapt to these changes—or face the potential of technology slowly killing their industries, Hambrick adds. “Kodak had the first digital camera, but for some reason it was too expensive; they didn’t think anyone was ever going to buy one. It wasn’t too many years after that, Kodak was bankrupt. Same with Blockbuster… They were the biggest movie rental company in the world, but… they were not paying attention, and [change] was happening.”

The Mixed Road

Autonomous technology faces obstacles beyond the investment of so many industries in the status quo, however. For one, the concept of a driverless car incites arguments over personal choice. Driving is a freedom that some may never be willing to fully relinquish—especially Americans, who often consider the “open road” their birthright. While the European Union has already cut auto accidents in half from its 2010 peak by deploying autonomous features, here in the U.S., “there’s more of an ownership culture,” Fraker notes.

But this technology is not about surrendering personal choice, he stresses. “It’s about having the machine drive with people… augmenting our own capabilities. Here’s a simple way of thinking about it: we can see [only] the direction our eyes are looking. The car, with these technologies, can see ten times that distance: 360 degrees, all the time.”

Even without everyone on board, just a handful of self-driving cars on the road improves safety for all. “One vehicle with this technology, surrounded by four vehicles without it, makes all five vehicles safer because of that increased situational awareness,” Fraker notes. With each additional car running autonomously, the compounding effect only enhances that safety net. Of course, some of the technology’s promised benefits—from a significant reduction in traffic densities to redrawing the need for traffic signals—will require that most, if not all, vehicles on the road be autonomous. But Fraker’s assured this mixed road is ahead.

“We know the human error rate and can predict how many accidents there are going to be today, and we have a pretty good idea where they’re going to be and when they’re going to happen,” he says. “Even though the technologies are still very much in development, if we took all the test vehicles… and rolled up the accumulated miles they’ve traveled without incident, right now we’re ten times better than a human.

“We know what we’re capable of, and we know what the potential is,” Fraker says. “But is that acceptable?”

Enabling Mobility

The applications of autonomous technologies may prove to extend far beyond the road itself. “For the first time, these technologies allow us to ask ourselves: ‘What do we want transportation to do for us that it’s not doing today?’” says Fraker, whose clients include public transit agencies curious about the effects on its industry. “This is not a technology that will affect the wealthy first and trickle down. If you put these technologies on a city bus and make that bus safer for everybody on board… this becomes a much more socially responsible deployment.”

And that, he adds, is one of the wonderful things about enabling autonomy. For Fraker, it strikes a very personal note. “I got into this because my adult autistic son started talking to me one day about what it would be like for him to be able to own a car, how different his life would be. There are a lot of us who are very passionate about making sure certain groups of people don’t get left behind… This is a true societal benefit across the socioeconomic spectrum.”

About 15 percent of U.S. households are not independent due to a mental or physical disability, Fraker says, in large part because they’re isolated. One can see how autonomous technology might transform that statistic, potentially enabling the blind, the elderly and those with other physical impairments to be safely mobile for a longer period of time. As Josh Hartung notes, “The car is the original mobile device.”

“This type of transportation—where you tell the car where to go and have it take you there—enables independence,” Fraker says. “This population suddenly becomes a contributor to social welfare systems, instead of dependent on it. Once you eliminate the accident and enable route planning, it is essentially rebooting personal transportation.

“Intelligent transportation is a cornerstone of all great civilizations,” he adds. “And as transportation has evolved, civilization has evolved… Everything from urban planning and design, to architecture and construction, to insurance and lending… become potential candidates for reinvention… if we change how we move from point A to point B.” iBi