Peoria’s maker movement has industry experts and amateur tinkerers alike exploring the new age of manufacturing.

Meet Peoria’s makers. It’s hard to know what to call them: artists, builders, engineers, programmers, designers…? Yes, says Clint LeClair, they are all of this—and more. As president of River City Labs, a volunteer-led 501c3, he oversees Peoria’s “makerspace”—a “home for makers, tinkerers, hackers and general warranty voiders alike.”

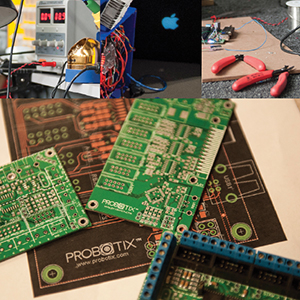

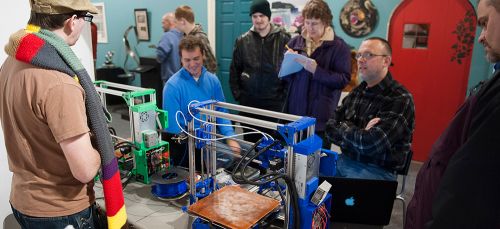

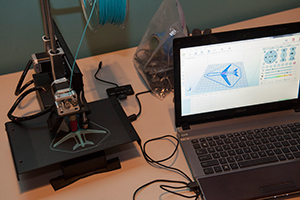

Tonight, the room has them all. It’s Build Night at the group’s community space on Southwest Adams Street. Every third Thursday and first Friday of the month, the public is invited to join members as they tweak sketches slated for 3D printers, toy with Arduino microprocessors, tinker with ball bearings and more. Though relatively new to Peoria, the scene is nothing new to LeClair, who recently moved here from New York City. “There was a makerspace in Brooklyn—I wanted one here,” he explains. “I came to find… that others in Peoria wanted a makerspace, too.” That’s when he met Joe Spanier.

Tonight, Spanier is scurrying about the studio, directing newcomers by interest—a matchmaker of sorts. He calls out to someone to “go find John,” who “has a kiln we can use for the ceramic printer.” Behind him, a group gathers around one of several 3D printers in the room. This one, available for just over $2,000 from the open-source company LulzBot, was assembled and modified by River City Labs members Josh Malavolti and Todd Crawford, with help from LulzBot's freely available blueprints. Around the corner, vice president Jay Babin shows off a cement gargoyle. The figurine was scanned into 3D software using an iPad Structure Sensor—the first 3D sensor for mobile devices—to produce a biodegradable red plastic replica, which will be used to create a mold to cast the model in aluminum.

Amidst this organized chaos, Spanier pauses to reflect on the group’s humble start in November 2013. “I was trying to find a group of people to start a makerspace for about four years,” he explains. “A friend… and I were giving a talk on 3D printing in Morton about a year ago, and at the end of the talk, I asked, ‘Who wants to start a makerspace?’ Basically everybody in the room raised their hands.”

Afterward, seven people stood outside for nearly three hours, fueled by adrenaline, brainstorming the possibilities. “After a while, it got too cold,” Spanier recalls, smiling. “We decided, ‘Okay, if you’re serious about this, show up in two weeks at Thirty-Thirty Coffee and we’ll talk more.’”

Not only did everyone show up, he says, each of them brought a friend. “It just snowballed from there.” While 3D printing was the catalyst, the group’s main objective was to find and create the space itself. “What we were really after was a place to work and to house tools, to collaborate and share ideas.”

Makers Reborn

The popularity of today’s maker culture owes a lot to the 2005 launch of California-based Make magazine and its subsequent flurry of maker faires—events celebrating the arts, crafts, engineering, science projects and the do-it-yourself (DIY) mindset. Their success jumpstarted a global “maker movement” of both hobbyists and professionals who bring the DIY mindset to leading-edge technologies. The makerspace—a physical location where people can network, share resources, collaborate and build—soon grew out of the movement, and makerspaces began to spring up in cities around the world.

The primary driver of this movement? Manufacturing is now within the realm of individuals—not just big business and industry. That wasn’t the case until recently, LeClair says. “The maker’s movement actually started through a Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency [DARPA] grant to Maker Media.” From those initial seeds, he says, the culture spread like a fast-moving pandemic: from the German Chaos Computer Club, “Europe’s largest association of hackers”; to Noisebridge, a nonprofit “hackerspace” in San Francisco; to NYC Resistor in Brooklyn and MIT’s Center for Bits and Atoms—a contagious outbreak of ideas.

This rapid evolution was enabled by the sudden affordability of hardware previously out of reach for hobbyists. For instance, CNC router (computer-controlled cutting machine) technology has been around since the 1940s, long before microprocessors were introduced. What’s different today is that the machines’ specialized, high-precision stepper motors are now commodity items made by the millions—and for cheap.

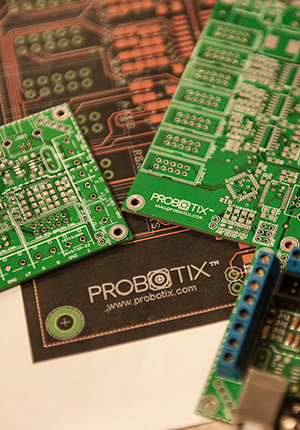

“You no longer have a proprietary control system,” explains Len Shelton, founder of Probotix, a Peoria company that specializes in CNC control systems. “They run off of a $300 computer using software that’s free and open source. Fifteen years ago, you’d have to spend $50,000 to get into CNC. Now you can get a commercial-quality machine for $5,000. That’s the big deal.”

The Modern Experiment

Len Shelton calls his company “a happy accident.” In 2005, while flipping through a magazine, he read about a guy who built a small CNC drilling machine to make circuit boards using parts he found on eBay. “I was like, ‘Wow, that is so cool. You can build a CNC machine in your house now.’

“At that time… they were moving all the manufacturing over to China,” he adds. “What little was left out there in California, they were tearing down assembly lines… and liquidating all that stuff on eBay. So you could buy these really nice, high-end components that might be $5,000 brand-new… for 50 bucks.” Using their eBay finds, tinkerers around the country began cobbling together these “Frankenstein CNC machines.” Shelton, too, was hooked. “I started making these little stepper motor controllers and selling them on eBay… just for fun.”

Shelton worked full-time at an Internet marketing company at the time, optimizing websites for search engines. Applying this expertise to his hobby, he easily beat the handful of others selling similar control systems by getting to the top of the search engines. “By about 2007, I figured out that I had a real business opportunity, so I decided to go ahead and incorporate.” The company officially launched in January 2008.

In its first month of business, Probotix did $20,000 in revenue—all out of Shelton’s basement and garage. Before long, he needed more space, and more hands. “In e-commerce, you would think it was all very anonymous. But our customers want to talk to us! As soon as I had somebody there to answer the phones, it just took off.” He quit his day job three months later, and still hasn’t had time to look back.

Learning by Doing

One of the important aspects of makerspaces, suggests the IT-focused nonprofit Educause, is that they are zones of self-directed, multidisciplinary learning. “Their hands-on character, coupled with the tools and raw materials that support invention, provide the ultimate workshop for the tinkerer and the perfect educational space for individuals who learn best by doing.”

For LeClair, it’s a great place to get one’s creative juices flowing and explore the possibilities of new technologies. He likens it to “1950s home economics.” An arduino, an open-source prototyping board, is “like the Singer sewing machine of the old days,” he says. “If you have an idea but don’t know how to make it work, you come to a place like this.”

Spanier offers an example. “I’m not very good at programming,” he admits. “But I am very good at building the things that need to be programmed. So when I need programming help, I have three or four guys I can walk up to… and they’ll probably have an answer for me.

“It’s also helpful to have somebody to bounce ideas off of as you’re trying to think through things,” he adds. “The idea might change significantly by the time you’re done, but usually it turns into something awesome.”

The only real rule governing participation at River City Labs is that all projects must be open-source, meaning their inner workings must be made freely available. “You can’t hide something and work on it in private,” LeClair explains. “You have to share it with the group. If you want to work in private, you’ve got your own home for that.”

This guideline also prevents the theft of ideas. “This is supposed to be a safe place to bring your ideas and ask questions about them. You should be able to do that without worrying that somebody’s going to run home and patent your idea before you have a chance to take it to market.”

For a field that’s so hands-on, there’s something rather intangible about the maker movement. Perhaps it’s the specialized knowledge and technical know-how, which may seem esoteric to the layperson. This type of creativity, however, requires very tangible equipment.

Kindred Spirits

Early one Saturday morning last year, Len Shelton hopped on a forklift and yanked ten large pallets of equipment out of his crowded warehouse and into the parking lot. The mound of gear consisted of old prototype machines and a variety of motors and controllers—components his company had tested over the years. Knowing its value, he didn’t want to throw the equipment out, but he knew he had no use for it. To maintain its remarkable growth spurt, Probotix needed to reclaim some of its warehouse space.

“It was a lot of really cool stuff,” Shelton says. “Some of it was kind of a work in progress… old, broken-down pieces of equipment that needed some work… which is exactly the kind of thing they need in a makerspace.” He got on the mailing list for River City Labs, and by the end of the day, the hobbyist group had mustered six pickup trucks to haul it all away.

“He said, ‘Tell you what. You guys are going to be a nonprofit,’” LeClair recalls Shelton saying. “And that was that.” This collection of “basically everything computer- and metalworking-related, plus a million ball bearings” is still being pored over by the group. “We’ll figure out how to use all of it someday,” LeClair assures.

Shelton was happy to help, as the mission of River City Labs reminded him of Probotix’ own beginnings. “We’re an example of a garage startup made possible by inexpensive prototyping and manufacturing tools,” he explains. “But we also make those same tools and help other small businesses. It blows my mind what some of our customers are out there making!”

He smiles as he describes one client’s line of wooden bow ties, made by laminating together exotic woods. “I’m not a bow-tie kind of guy, but if I ever wore one, I’d want a wooden one,” Shelton laughs, his voice competing with the whirr of machinery in Probotix’ warehouse on North Industrial Road. The company started in about half the space, he explains. It now employs eight full-time and a few part-time employees—and its evolution shares the DIY approach that’s manifest at River City Labs. Just call it the maker culture.

At first, Probotix only sold control systems; eventually, Shelton began looking for another CNC machine to make additional parts for those systems. “I found a guy who was building this machine down in southern Georgia… a kit [for] user assembly.” Now marketed as the FireBall V90 Router Machine Kit, it can be mounted with rotary cutting tools to cut wood, plastic, carbon fiber, fiberglass, some soft aluminums and brass—with a precision and repeatability you can’t get by hand. Struck by the product’s ease and simplicity, Shelton approached the builder. “We had the electronic control system… the motors and power supplies, and he had the machine. It was like the perfect marriage.”

Beginning as a product reseller, Probotix quickly took over the manufacture of some of the kit’s parts in order to cut shipping costs. As orders poured in, the company eventually bought out the one-man-shop’s machine designs, branding and website. “We brought that all in-house, and we’ve sold tons of them… all over the world. We pre-assemble them, then we tear them down and put them in a box the Postal Service will carry.”

While the FireBall V90 appeals to hobbyists, the company’s FireBall Meteor, Comet and Nebula models come fully assembled and calibrated, attractive to larger industrialists. With twice the work envelope, the Meteor is Probotix’ top seller, suitable for building guitars; making clocks, plaques and signs; and constructing parts for radio-controlled aircraft. “[We’re] no longer catering just to the hobby community,” Shelton notes. “We actually sell mostly to small businesses [and] universities… They don’t want to mess around with building a machine from a kit. They just want to pull it out of the crate.”

In addition to CNC routers and control systems, Probotix recently delved into 3D printing as a reseller of the Vision Plus, a model designed and built by a friend of Shelton’s. He’s optimistic about consumer interest. “I’m glad to see there’s finally a maker movement going on in Peoria,” he stresses. “Peoria’s always been about ten years behind with music and fashion [and] things. Late bloomers,” he adds with a grin.

Fanning the Flames

“One of the first things I did when I moved here was find a makerspace,” says Neil Moloney. A recent Peoria transplant from Virginia, he was part of a makerspace on the East Coast that tripled in size from 2012 to 2014. Craving those collaborative energies, Moloney found personal respite at River City Labs. But for the community at large, he adds, these spaces can offer much more.

“STEM [science, technology, engineering and math] is not as strong as it has been in the past,” he suggests. “A lot of kids growing up don’t know how to use a screwdriver… [or] a wrench.” Back in Virginia, Moloney was involved in “take-apart” days, where members would teach kids how to use tools. “That kind of training—that hands-on stuff—is really absent in a lot of programs—not just locally, [but] around the globe.”

Once a makerspace becomes established, that sort of community outreach can happen, he suggests. As word gets out to the general public, “that’s when people generally come to the makerspaces and say, ‘Hey, can you do something for my Boy Scout troop or for my softball team?’” And those ideas then spread further.

Members of River City Labs have already presented at large, corporate-sponsored maker faires, as well as numerous local events, including a Girl Scouts outing where volunteers manned a booth on button-cell batteries and LEDs. Other ideas are in the works, but LeClair hesitates to list them all. “I don’t want any hype,” he declares. “There’s a lot of hype everywhere—and I only want content. That’s why most people don’t hear about River City Labs. We’d rather you be wowed and actually do something with that ‘wow,’ than hear about it and be let down.”

“If somebody wants to learn about something, this is the place to come,” Spanier adds. “We’re really open to sharing and exploring new ideas. The biggest argument I get from people [for] not coming here, is ‘Oh, well, I don’t know anything about that.’ And that’s ridiculous. That’s like not going to the gym because you’re not fit and strong. You go to the gym to get fit and strong! You come here to learn!”

“It’s a lot simpler than you think,” says LeClair. “All it comes down to is this: if you want to be creative… come in. The one thing that’s different in a makerspace than anywhere else is that you want to celebrate the failures. Fail fast, but fail smart… Our goal is to provide a safe space to go and learn fast.”

Because for makers, failure is just tinkering; it’s part of the journey. There’s a revolution underway in the world of manufacturing, and the makers are at its center. And with boundless opportunities on the horizon, they now have a home in Peoria. iBi

To learn more about River City Labs, visit rivercitylabs.org. For more information on Probotix, visit probotix.com.