Behind the scenes of the world-class foundry in Mapleton…

When you first think of Caterpillar, the likely picture that comes to mind is huge, yellow iron. Within that massive piece of equipment is the machine’s heartbeat: its engine. Cat engines are used all over the world in a range of applications—powering Cat mining trucks, locomotives, gensets and ocean vessels; in use on hydraulic fracturing sites; and more—and many of those engines come to life right in our own backyard.

Turning Sand Into Molds

The Mapleton facility, led by Gary Bevilacqua, produces 3500 and 3600 series engines, as well as C175 engines. During the course of my career, I’ve had the privilege to visit the facility many times. It’s evident to see why Mapleton is considered a critical part of Caterpillar. Gary and his team have worked extremely hard to build a world-class foundry that serves as the leader in foundry technology and innovation.

You may ask, what exactly is a foundry? Founding is one of four major methods of forming metal into useful shapes, including our large engine cores. The other three are machining, welding and forging. Founding involves the melting of metal that is then poured into a temporary mold. The temporary mold holds the fluid metal in the desired position until solidification. Once solidification occurs—in Mapleton’s case—a new engine core is brought to life.

But the whole process begins with sand for the core molds. Up to 500 tons of sand are trucked each day into Mapleton—the only foundry of its size in all of Caterpillar. Technicians like Dan Bump, a core maker at the facility since 2009, are skilled at turning sand into molds. It takes 1,200 pounds of sand to create a 3500 engine block core. Those 3500 cores make their way from Dan’s station, ultimately creating an engine block that gets shipped to Lafayette, Indiana, where they’re assembled for delivery around the world.

“I love the atmosphere and the people I get to work with every day,” says Bump. “There are four guys who work on the core deck. Two operators handle 62,000 pounds of sand in this station a day. The cores are like slices of bread—it’s amazing how it all fits together.”

The cores must be strong enough to withstand the entire process, and it takes 10 cores to create a mold for a 3500 series engine block. A mixture of sand and resin holds it all together. The cores come out of an oven and appear “baked” at this point. The team at this station acts as the last set of eyes, checking for defects, until the casting is poured at the next station. In the last few years, these technicians have shortened cycle times by speeding up the belt while maintaining quality. Before moving to the next phase, the technicians place filters in the pour base for the cores to catch any impurities and allow the purest iron to later flow down when they enter the pour zone.

Pouring the Iron

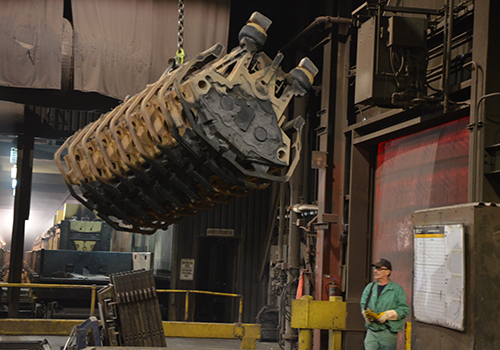

Mapleton technicians also melt iron (up to 500 tons each day) into tight specifications that eventually become cylinder blocks, heads and liners used in products from engines to powertrains and trucks to locomotives. The first pour of melted iron in the current factory occurred in 1978. More than 35 years later, 650 employees—including Scott Crabtree, a 30-year employee who has been pouring iron for at least 20 of those years—are still ensuring quality castings go out the door every day.

A large “ladle” that resembles a huge teapot holds up to 48,000 pounds of iron at about 2,500 degrees. Three employees operate this station wearing full fire protection gear. After ensuring the temperature is just right, Crabtree operates a crane to transfer the ladle to the mold. Another employee operates an automatic conveyor system that pushes the core through to receive the pour, and the third technician then pours the iron into the pour base for the core. Sparks fly out, similar to massive sparklers.

“The crane is a marvel for its power,” Crabtree says. “You can move it a quarter of an inch if you need to do so.”

This is where Caterpillar pours all of the blocks for its 3500 and C175 engines. “These operators must think together,” says Leonard Matheny, environmental, health and safety manager for the facility. “They’re very in synch, and they must get the pour just right. The trust level is huge. The iron pourer’s back is to the other operators, so they must rely on each other. I’ve been in foundries all around the world, and I’ve never seen people better work in tandem than Mapleton.”

Once solidification of the iron within the core occurs, the outer core casing is removed in a “shake out” area and the core becomes broken down. A technician then shot-blasts the block to remove any remaining sand from the sand/resin core and reveal a shiny engine block. You can feel the heat radiating off the castings, which are still about 400 degrees. Yet, it’s beginning to look more like an engine. After blasting, the blocks enter a chipping and grinding area to file away imperfections. Then, the blocks are heated during a stress relief process to eliminate the risk of stress cracks. Afterwards, the blocks are shipped to the appropriate facility, where they are then machined.

In addition to casting production, Mapleton added 200,000 square feet of machining over the past few years. Machining is focused on rough machining 3500 and C175 blocks, as well as complete machining of cylinder heads and liners.

“This is a unique organization that is embracing technological change whole, and still exercising a very fundamental and American manufacturing process,” says Gary Bevilacqua, facility manager for the Mapleton foundry. “The components produced by the cast metals organization—blocks, heads and liners—are core to our products’ durability, which is essential to Caterpillar customers. I’m proud to lead an organization that passionately carries this responsibility.” iBi

Henry Vicary is community relations manager for Caterpillar Inc.