“Men make history, and not the other way around. In periods where there is no leadership, society stands still. Progress occurs when courageous, skillful leaders seize the opportunity to change things for the better.” —President Harry S. Truman

The year was 1918. Many union members were meeting in back rooms in secret to transact their business. It was during this time that the union members of the Peoria Trades and Labor Assembly realized that organized labor needed a place to have one centralized meeting hall. “We need to concentrate our strength and direct our efforts toward a desired end,” wrote the Assembly.

On January 21, 1918, the progressive men of the Assembly established the Peoria Labor Temple Association of Peoria, issuing 2,100 shares at $10 each, sold to “union men only.” The purpose of the new organization was:

“To unify and further the aims of the Union Labor movement in the City of Peoria, Illinois, and vicinity, and for that purpose to afford places of meeting and facilities for recreation, social interaction and education for members of Labor Unions, to disseminate knowledge and information, relating to matters in which Labor is interested, and to maintain and operate a building or buildings in which such functions may be pursued.”

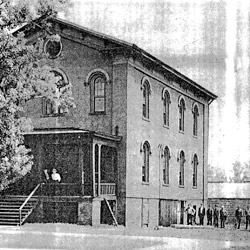

By October 1920, the Assembly purchased the old Peoria Female Academy building for $12,500. The building was constructed before 1856 and graduated the first class of Peoria High School that same year. In later years, it was used as the Third District school and was also the first Irving Elementary School. At the time, the building was owned by Carpenters Local 183, who had purchased the site at the turn of the century. The Carpenters Local was very generous, allowing many labor unions in Peoria to use the site for meetings during the early 1900s.

After purchasing the building, a storm damaged the roof and front of the building. The Association decided to build another labor temple as a tribute to organized labor, and the old school was demolished to make way for the new project. To help with the transition, the Association built a concrete-block garage at the back of the property at 400 NE Jefferson to take care of union business until the new labor temple was constructed.

In April 1925, construction began on the new Peoria Labor Temple. Veder Storry, a member of Carpenters Local 183 and secretary-treasurer of the Association, served as the superintendent on the project. During the day, he worked diligently on the $110,000 project, and in the evenings, he sold stock to help pay for it.

After several years of hard work, the Peoria Labor Temple Association dedicated the building on Labor Day in 1925. “Peoria labor organizations at last realized the fruition of their dreams and now have a home of their own, financed by the labor movement of Peoria. The Carpenters Union should be given great credit for their efforts in the movement,” stated the article from the Sept. 4th issue of the Peoria Labor Gazette.

Dignitaries in attendance included: President of the American Federation of Labor William Green, State Representative David McClugage, Secretary of the State Federation of Labor Victor Olander, President of the Illinois State Federation of Labor John H. Walker, Speaker of the House of Representatives Robert Scholes, and Illinois Miners President Frank Farrington. More than 10,000 union members attended the dedication, which included the placing of the cornerstone and plenty of spirited speeches.

In 1944, the Association became the Peoria Labor Temple Association, reorganizing to take advantage of the Non-Profit Corporation Act of Illinois. The “new” group issued $62,000 of new bonds to labor unions only, using the money to pay off the original stockholders of 1918 and the promissory note on the building.

In July 1958, the Association paid off these bonds. That same year, it purchased the Labor Temple News, now The Labor Paper. To finalize that purchase and pay off the remaining bonds, a new set of 20-year bonds totaling $48,000 was issued to labor unions.

Over the next few decades, the Labor Temple expanded its ownership by purchasing two lots next to the original property, increasing its land to total one quarter of a city block. Over the next several years, the buildings on those lots were demolished to create more parking spaces.

By the 1970s and ‘80s, a number of unions had moved out of the Labor Temple into their own buildings. Hall rental had also decreased greatly as unions moved their meetings to more modern union halls. In order to keep its tenants, the Association undertook a major renovation of the building in 1975 at a cost of $220,000. New windows were installed, a new roof was put on, and central air conditioning was added. The building got a fresh coat of paint and dropped ceilings. At the same time, tenants invested about $50,000 renovating their offices. The renovation resulted in more tenants and began re-establishing the Labor Temple as a “house of labor.”

Yet according to John Martin, former secretary-treasurer of the Association, “A number of unions started folding in the 1980s and there was a lot of movement of groups in and out.” In the late ‘80s, the Labor Temple Association realized that something again had to be done about the building’s disrepair. “We came to the conclusion that we needed to make major improvements or abandon the building,” said Martin. “We looked at building property…but we came to the conclusion…to renovate. That project was over a million dollars, and we got that put together in 1991.”

Yet according to John Martin, former secretary-treasurer of the Association, “A number of unions started folding in the 1980s and there was a lot of movement of groups in and out.” In the late ‘80s, the Labor Temple Association realized that something again had to be done about the building’s disrepair. “We came to the conclusion that we needed to make major improvements or abandon the building,” said Martin. “We looked at building property…but we came to the conclusion…to renovate. That project was over a million dollars, and we got that put together in 1991.”

The recorded history of the Peoria labor movement became apparent during the renovation. “When we got into the process of remodeling, as unions folded, they had tons of records that were never thrown out,” added Martin. “We decided that we couldn’t keep it all, but we wanted to keep the remnants...little bits and pieces that were visually appealing. We pulled old banners, placards, badges, old photos and put them on walls and in cabinets for display. We also have in the back entrance the cornerstone contents from 1925.” The rest of the recorded history of Peoria labor was donated to the Illinois Labor History Society in Chicago.

Since the renovation, the Labor Temple has been in constant financial turmoil. Martin was one of the main reasons the Labor Temple survived during those years. “We were constantly behind the eight-ball for the next eight to nine years. We were always able to keep afloat, but we were never able to put aside money for a rainy day—we just had enough revenue to support it.”

Mike Everett, current president of the Labor Temple Association and business manager for Electrical Workers (IBEW) Local 34, has seen a constant battle to keep the Labor Temple open and running. “One of the first acts as president was to sign the note for $1.6 million to renovate the place, and I was really wondering what these guys were doing to me when I did that. But the Association saw the value in the Labor Temple. It is not just an old building built in 1925—it is the identity of organized labor in Peoria Illinois.

In 2000, the Association decided to refinance. “We refinanced the building again, just to make the payments lower and to make some improvements,” said Martin. These improvements included the parking lot, a fresh coat of paint, a new fence around the property, repairing and replacing windows, and a new roof.

The future of the Temple seems to always be in jeopardy. “I would assume the Temple will always be there,” Martin said. “The critical thing is trying to figure out financially and structurally how to take care of the building as unions are diminishing. Local unions either need to make a commitment to come back to the building or the ones there need to make a larger commitment to the building. It is always going to be a struggle.”

Everett summed it up. “There are only about 60 labor temples [in the United States] left. It is the identity for unions that reside here and for every union that does not reside here,” he noted. “When the media or government want to talk to labor or want to know how labor feels about the issues, they come here. This is really the anchor of the labor movement, and we would never really realize the value of the building until it was gone, and then it would be too late.” iBi