Johnny, get your gun, get your gun, get your gun.

Johnny, show the “Hun” you're a son-of-a-gun.

Hoist the flag and let her fly

Yankee Doodle do or die.

Over there, over there

Send the word, send the word over there

That the Yanks are coming

The Yanks are coming

The drums rum-tumming

Everywhere

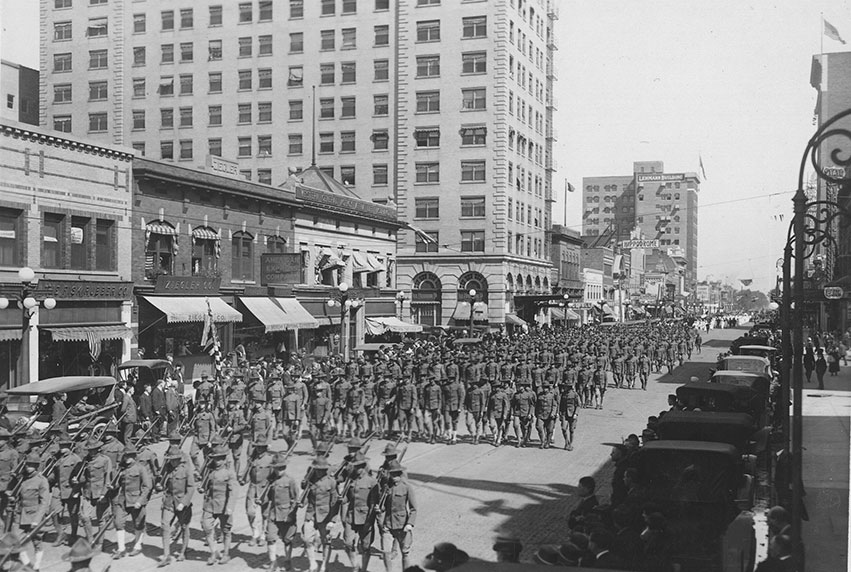

These words from George M. Cohan’s 1917 song “Over There” appear to reflect the sentiment of the majority of Peorians during U.S. involvement in World War I. However, when the “Great War” began in 1914, Peorians were not as eager to get their guns and fight the “Hun” as they would become in later years.

Shifting from Neutrality

Shifting from Neutrality

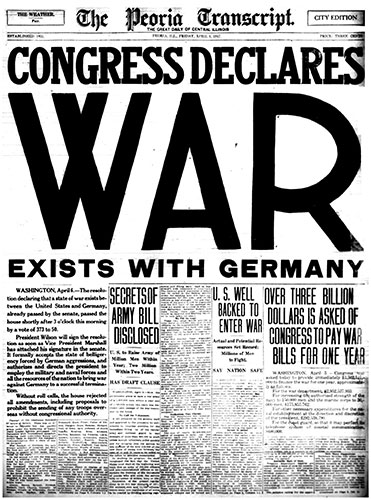

Accounts from early 1915 discuss the refusal of Keystone Steel & Wire to supply several thousand tons of “barbed wire entanglements” and 100,000 “airplane death darts” to France. Competing rationales were given. One was that Keystone could not undertake huge contracts in addition to their regular outputs; another was that it would be “an infraction of neutrality.” Neutrality was the stated policy of the United States from the war’s beginning until April of 1917, when war was declared by Congress. It’s unclear if Keystone’s refusal was for one or both reasons. A third explanation is that the owners of Keystone had German roots, as did many in the Peoria area.

The 1900 U.S. Census shows 19,483 Germans in Peoria. The 1910 Census for Peoria lists 13,609 individuals with both parents hailing from Germany. This was at a time when the entire population of Peoria was not quite 70,000. The entire United States had a population of 92 million in 1910, with around four million having been born in either Germany or the Austro-Hungarian Empire (the Central Powers). Britain, France and Russia (the Allies), combined, supplied just under three million foreign-born from those respective countries. And these numbers do not include any succeeding generations.

At the turn of the 20th century, Peoria had German newspapers, German churches, German banks and German restaurants, along with German clubs and organizations of many varieties. In 1906, a book was published in German, entitled A Popular History of the City of Peoria. Written by a Lutheran pastor by the name of Frederich Bess, it goes into detail describing not only Peoria at the turn of the century, but also the continuing contributions made by Peorians with German ancestry. It is obvious to even the casual historian that those Peorians who claimed German lineage were not only proud Peorians, but proud of their German heritage as well.

In the early years of World War I, those same German Peorians made their sentiments about the war clear, as reported in Peoria’s newspapers. In May of 1915, Peorians of German descent called for an embargo on all munitions shipments from the U.S. to belligerents. That September, Peorians who were labeled German sympathizers protested to President Wilson, asking that the United States not loan England and her allies money for their war efforts.

In the early years of World War I, those same German Peorians made their sentiments about the war clear, as reported in Peoria’s newspapers. In May of 1915, Peorians of German descent called for an embargo on all munitions shipments from the U.S. to belligerents. That September, Peorians who were labeled German sympathizers protested to President Wilson, asking that the United States not loan England and her allies money for their war efforts.

As reports of the behavior of German troops in the war began to reach our shores —augmented by Allied propaganda—American opinion shifted to the cause of the Allies and against Germany. This behavior, along with the German naval blockade of Great Britain through the use of unrestricted submarine warfare, eventually led to the U.S. declaration of war on Germany. As the tide of public opinion turned in the country, it also turned in Peoria.

Holt Inspires the “Land Battleship”

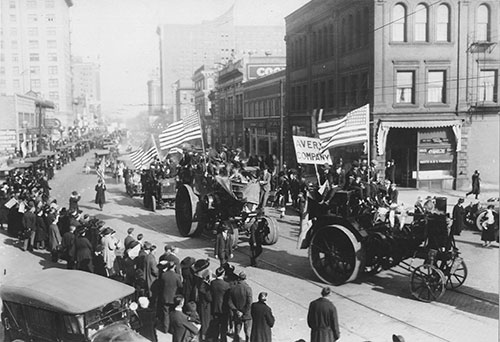

Prior to the shift in public opinion, a major Peoria company was already providing products for use in the war overseas. That company was the Holt Manufacturing Company, parent of the Caterpillar tractor. In its East Peoria offices, just after the war’s end, there were several framed photographs of Holt Caterpillars doing work such as pulling artillery or supplies over the battlefields of Europe. The caption beneath the photographs was “Getting a ‘Holt’ on the Hun.”

Despite this proud proclamation made in 1919, there is evidence that Holts were being used by all of the major combatants in the Great War. Holt Vice President Murray Baker was quoted early in the war saying he knew that all major warring parties in the World War had purchased tractors built by Holt. These tractors were being used to tow heavy guns and material on both sides.

Despite this proud proclamation made in 1919, there is evidence that Holts were being used by all of the major combatants in the Great War. Holt Vice President Murray Baker was quoted early in the war saying he knew that all major warring parties in the World War had purchased tractors built by Holt. These tractors were being used to tow heavy guns and material on both sides.

Before the U.S. declaration of war in 1917, news accounts from across the country made the Caterpillar tractor famous for its role as the basis for the newly-introduced British tank, but erroneously so. These accounts start appearing in September of 1916 and discuss the use of the Holt Caterpillar tractor as the basis for a “land battleship,” “Juggernaut” or simply a “tank,” the term by which it is known today. The British tank had recently become famous for its actions in the Battle of the Somme—the first time it was used in combat. But contrary to these early news stories, the Holt Caterpillar was not the basis for the British tank, only the inspiration.

Interestingly, although the British did not use underpinnings of the Holt for their tanks, the Central Powers and France did. A dealership in Austria was the sole distributor prior to the war for all of Austria and Germany, providing Holt tractors that ultimately ended up in the hands of the Central Powers for military use. There was also a factory behind enemy lines that was licensed to use the Holt tractor design. These tractors, while used to tow weapons and supplies as on the Allied side, were the basis for the only functional German tank of the war, the A7, which used a copied version of the Holt’s running gear.

Despite the use of the Holt Caterpillar tractor by both the Central Powers and the Allies, the majority were ordered and used by the British prior to American involvement. Murray Baker stated that by 1916 there had been around 1,000 sold to the British government. Once the U.S. joined the Allies in 1917, Holt production increased rapidly—along with the size of its factory in East Peoria. By the end of the war, thousands of tractors were built for use by U.S. and Allied forces.

Anti-German Sentiment in Peoria

1917 also saw changes in the way Peorians felt about those with a German cultural background, as reflected in the pages of Peoria papers. Days before the start of U.S. involvement in the war on March 31, 1917, federal troops were sent to guard the Holt factory in East Peoria against possible sabotage. A few days after the U.S. declaration of war, Peoria wireless radio sets were ordered dismantled for fear that German sympathizers would use them to report on confidential war preparations. (This was also happening across the nation.)

In September of that year, a Circuit Court judge, while addressing 115 military recruits in Peoria, alluded to the threat of hanging any pro-German “reservists” in America. In November, U.S. government officials raided the offices of the Peoria German-language Die Sonne newspaper, as well as the homes of its owners. December 10th saw the Lincoln Grade School superintendent discharged from his position for “pro-German utterances.”

The following year, anti-German sentiment in Peoria took a fever pitch, with a culmination appearing around the first anniversary of the U.S. declaration of war. In the month of April alone, the following items appeared in Peoria papers:

- The Peoria County Board of Supervisors and Peoria City Council stopped printing proceedings in the German newspaper, Die Sonne;

- The Commercial German National Bank dropped the word “German” from its name;

- Peoria clubs and organizations passed strong resolutions against pro-German propaganda and pledged to “wage war” on disloyalty;

- Peoria representatives from the State Council of Defense passed resolutions that would force all German language material to be discontinued;

- The Board of Education voted to eliminate all German language instruction immediately;

- The Peoria County Grand Jury urged a “Loyal Citizens Act” and the American Protective League formed a branch in Peoria with “the aim of meeting secret treason, ferreting it out and scotching the viper of pro-Germanism and disloyalty.”

The World War Soldiers & Sailors of Averyville Monument at the base of Grandview Drive

Return to Normalcy

When the war was over, over there, Johnny Yank came back to Peoria and cities all over America, taking jobs in factories like Keystone and Holt. Anti-German feelings subsided, and Americans made an attempt to “Return to Normalcy,” as reflected in the slogan of Warren G. Harding’s successful 1920 presidential campaign. Peoria, the United States and the world were left forever altered nonetheless.

Regardless of the anti-German sentiment that swept Peoria during the First World War, and then again to a lesser extent during World War II, Peoria’s Germanic heritage carries on. The Peoria-based German-American Central Society still has a strong presence in Peoria, sponsoring numerous events throughout the year. The organization has roots in the Concordia Singing Society, formed in Peoria more than 150 years ago. The German-American Central Society has stated that the “purpose and objectives of the corporation shall be to promote German culture in the Peoria, Illinois area, including singing, sports and good fellowship. Members of good character, especially those of German background and/or ancestry, are encouraged to become involved.” iBi

Chris Farris is reference assistant librarian at the Peoria Public Library Local History and Genealogy Department. Mary Spengler, reference assistant at the Peoria Public Library North Branch, aided in the research for this article.