A healthcare entrepreneur plans to put his money where his mouth is—and virtually no part of the Heights will be left untouched.

You could say that Kim Blickenstaff—the San Diego businessman promising to transform the Village of Peoria Heights—is not just any developer.

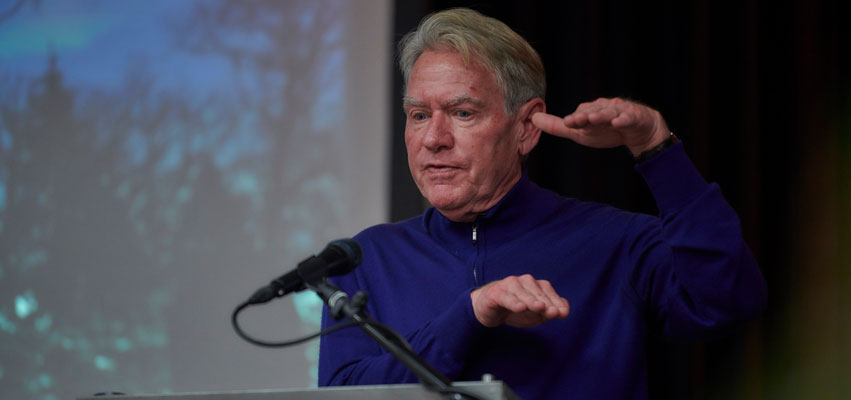

Asked at his December 2018 press conference by Peoria County Board Chairman Andrew Rand how he could move forward on multiple promised investments with “no government subsidies, no government incentives, no local tax breaks”—contrary to prevailing practice in many quarters—Blickenstaff dispelled all doubts that he might be cut from anybody’s cloth but his own.

“Well, the problem with developers… it’s the old Donald Trump formula,” he stated. “You go out and get somebody’s land, and then you borrow a bank’s money… You come up with a project and it costs twice as much as you thought and takes twice as long, and it collapses. The bank ends up owning the land.

“That’s what developers classically do,” Blickenstaff continued. “They don’t put their own capital to work. If you don’t have equity in one of these things, you’re going to end up with that every time. So I’m going to put equity into this.”

It was the applause line of the afternoon, which only grew louder when he added this: “I’ve got to put my money somewhere. Why not here?” Why not here, indeed?

Local Boy Makes Good

“Here,” in this case, is home for Blickenstaff, who—when asked why a San Diego guy would invest in central Illinois—is fond of saying, “I’m not from California. I’m from Spring Bay.”

That’s where he grew up, the fourth of five children of Wyverne Augustus and Betty Jayne Blickenstaff. His father was a Caterpillar manager, his mother a former stage dancer in the Big Band era who devoted her adult life to corralling five kids intent on exploring every inch of the 32 Woodford County acres they labeled Woodtick Hill.

While it might seem that Blickenstaff has come on the scene out of nowhere, his central Illinois roots run deep. He would graduate from East Peoria Community High School in 1970, then from Illinois Central College two years later before matriculating at Loyola University of Chicago, where he earned both bachelor’s and master’s degrees. From there, he launched a finance career at Baxter, the Chicago-area healthcare company. But he had choices at the time.

“I looked at banking,” he explains. “Paper was big. Steel was big in Chicago.” It was in healthcare, however, that Blickenstaff “saw modern architecture” and “the potential high-growth environment,” accompanied by the sense that “this is not classic inhumane capitalism.

“Ultimately what you’re doing is something that helps people,” he notes. “This is where everybody wins. The quality-of-life improvement—that’s what it’s really all about.” He had three offers, “thought Baxter was the best one, and I was right.”

“The intent I have is to listen,” Blickenstaff stresses. “I’m not imposing anything.” That begins with preserving the character and vitality, charm and history of the Heights he found so irresistible in the first place.

Alas, it also turned out to be a high-stress environment with significant turnover. There were opportunities to do much the same work—creating long-term business plans, seeking high-return investments, building realistic budgets, analyzing economic trends and satisfying demanding bosses—elsewhere, in a far warmer climate. Blickenstaff also had the entrepreneurial itch, and he was ready to scratch it.

“It was not a hard choice to make,” he says of his 1981 move to California, first to work at a pioneering company called Hybritech, then Biosite, then Medivations, before ultimately landing at Tandem Diabetes Care, where he now serves as president and CEO. Along the way, he witnessed a pattern that tends to define the startup world—round up some capital, start a company around a promising new technology, work hard to grow it, sell it at a big profit a few years down the road. He also noticed another pattern: “I watched all the top guys get rich, and I didn’t get rich.”

Early on, a mentor—and he’s had many, ticking off their names—advised him that his career would best be served by leaving the financial side, learning marketing and running the place. So that’s what he did. Of course there were hiccups along the way: challenging regulatory environments, product recalls, hostile takeover attempts. But all in all, the 66-year-old Blickenstaff’s career has been a chain of success stories.

“What motivates me is ultimately being right when everybody says you’re wrong,” he says. Then as now, he proved himself a different sort of bird. “I’ve never been the sell-it-quick kind of guy. I’m a bit different that way. Most don’t want the hassle of building a company. That part I love… That’s the thrill to me.

“I was with Biosite 18 years—that’s a long time for a startup CEO.” Tandem, he adds, “is essentially my last company.” All that’s come before has prepared him well for the present. “What I’ve learned is applicable to what we want to try to do in the Heights … I’d rather be out front jumpstarting it.”

The new Betty Jayne Brimmer Center for the Performing Arts had its grand opening in February 2019.

A Flurry of Projects

And so, this healthcare entrepreneur—equal parts free-market throwback and can-do visionary—is putting his money where his mouth is. For starters, the Betty Jayne Brimmer Center for the Performing Arts—the former Kelly Avenue Library—had its grand opening on February 2, 2019, with an eight-band concert that doubled as a fundraiser for local music education efforts. It was a kickoff true to what Blickenstaff foresees as the facility’s mission.

“I knew it was going to work as a community center” when he first planted eyes on it, he says. He envisions regular concerts, dinner theater, film presentations, soapbox lecture events, karaoke nights, etc.—a cultural gathering place, inside and out, when the weather is accommodating.

This initial development is also an example of how family informs and inspires Blickenstaff. He speaks with great pride and affection about the mother whose name adorns the building—the woman whose pre-marriage-and-family entertainment career included a prominent role in the Benny and Betty Fox performance troupe as “the world’s most beautiful acrobatic dancer.” Her photo hangs just inside the doorway.

That the place is allegedly haunted by a friendly ghost—believed to be Florence, the former librarian, “hair pulled back in a bun, elegant long dress,” already witnessed by more than a few—only enhances the project’s appeal to him. It doesn’t hurt that the building was designed by the late architect Richard L. Doyle, who left his mark across central Illinois—starting with the iconic former Robertson Memorial Field House at Bradley University, and nowhere more than in Peoria Heights, where Tower Park, Village Hall and the Congregational Church remain among his legacy contributions.

Blickenstaff has become a fan of “RLD,” a practitioner of mid-century modern design, whom he describes as a cross between Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Frank Lloyd Wright. Don’t get this architecture nerd started on the floating staircases and globe lighting fixtures that are the personal signatures of Doyle’s work—or how Doyle’s additional skills as a structural engineer produced exceedingly functional buildings that were not only attractive, but have stood the test of time. He caught the architecture bug while building Biosite’s California headquarters, especially falling for the Bauhaus movement he encountered on frequent trips to Germany.

Perhaps not coincidentally, then, Blickenstaff also has his sights set on another Doyle project: the Prospect Mall office complex at 4617 N. Prospect Road, which in the not-too-distant future will become a 50- to 55-room boutique hotel. He has purchased the property and expects work to begin on it “the middle of next summer.”

Above, architect Richard Doyle’s original design of Prospect Mall. Below, a conceptual drawing of the new Atrium Hotel. The complex at 4617 N. Prospect Road was originally envisioned as a two-story structure. Blickenstaff plans to build that second floor while retaining the look and feel of its most distinctive feature, converting the outdoor plaza into an atrium.

The building was originally envisioned as a two-story structure, and Blickenstaff will build that second floor, while retaining the look and feel of its most distinctive feature; hence its name: The Atrium Hotel. Expect a rooftop terrace and ground-floor storefronts, perhaps a day spa or a breakfast eatery. Behind the building, there’s room to expand its footprint into what is now a parking lot. An expansive garden may highlight the property. And he’d like “as much glass as possible,” to give the project an almost “translucent” feel.

The building was originally envisioned as a two-story structure, and Blickenstaff will build that second floor, while retaining the look and feel of its most distinctive feature; hence its name: The Atrium Hotel. Expect a rooftop terrace and ground-floor storefronts, perhaps a day spa or a breakfast eatery. Behind the building, there’s room to expand its footprint into what is now a parking lot. An expansive garden may highlight the property. And he’d like “as much glass as possible,” to give the project an almost “translucent” feel.

Blickenstaff likens The Atrium to the reinvention of the old Imperial 400 Motel in Bozeman, Montana—abandoned for years before being resurrected as The Lark. “You can’t get a room in that place now,” he notes.

“This was the first thing the mayor asked me about,” Blickenstaff recalls of his initial meeting with Peoria Heights Mayor Mike Phelan. “I said, ‘I know. I stayed at the Embassy Suites [in East Peoria], but I want to stay in the Heights.’”

Meanwhile, Blickenstaff is purchasing the former Grayboy Kawasaki site at 4426 N. Prospect Road and an adjoining lot from the Village of Peoria Heights. Soon, the building will be demolished to make way for his Grayboy Plaza Lofts. Ultimately, he could have close to an entire block to play with here, producing 10 residential units of 2,500 square feet apiece (one of which he’ll call his own) spread across five structures, with underground parking and ground-floor specialty retail.

This will be a state-of-the-art green development, with a rainwater capture system to satisfy abundant vegetation around the property. Reclaimed wooden beams and glass will dominate the design, producing essentially a see-through structure that will be “warm in the winter, cool in the summer,” again with rooftop terraces permitting residents to look out over the colorful, lively street scenes below. He is especially sensitive to preserving the sight lines to Trefzger’s Bakery, another local landmark behind the property.

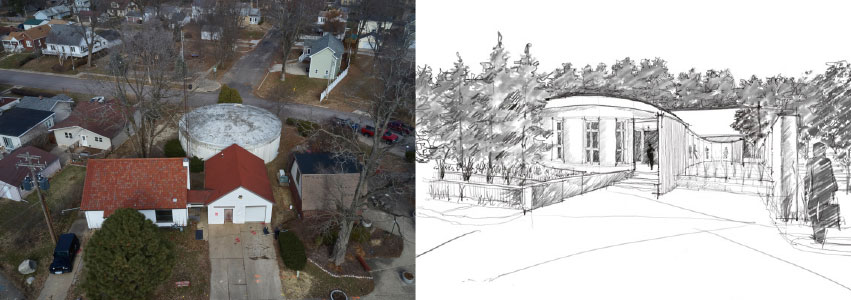

In late January, Blickenstaff also entered into a lease-with-an-option-to-buy arrangement with Peoria Heights for what is known as the Pump House property at the corner of Kingman and Euclid, just across from the village’s landmark Tower Park. He will be renovating the structures—initially constructed as a waterworks plant in 1934 by the Works Progress Administration under President Franklin Roosevelt, who was trying desperately to revive a Great Depression economy. The working concept is for “a quaint neighborhood restaurant” named for the original builders, the Mehlenbeck brothers.

Above left, aerial view of the Pump House property, constructed as a waterworks plant in 1934. The round concrete building once served as a village water tank. At right, a rendering of the former water tank shows Blickenstaff’s vision for the Pump House property, anchored by a quaint neighborhood restaurant, outdoor seating and a courtyard terrace.

The most challenging part of this development will likely be converting the round, thick concrete building that once served as a village water tank, which Blickenstaff described as a “bunker… structurally a bomb shelter.” He wishes to fit into the existing neighborhood, with plans to provide fencing and green buffers, along with non-intrusive lighting. All in all, it will be a “very tasteful,” attractive, fun place that “will be a good neighbor,” he promises.

Finally, at least until he gets restless and tackles something else, Blickenstaff is moving forward on two other additions to his roster of potential game-changers.

First, he has purchased the four-story Pabst building at the corner of Prospect and Seiberling, which largely will remain an office building in a community where such space is in demand. But he’s also exploring a few tweaks here and there, perhaps resurrecting something akin to the former brewery’s legendary and long-gone hospitality suite, the 33 Room.

Second, Blickenstaff will own the current Sav-A-Lot grocery property at 4425 N. Prospect, which he intends to develop into a local market—think Whole Foods Lite—though it could evolve into a larger facility of compatible mixed uses.

Blickenstaff recently purchased the Pabst building at the corner of Prospect and Seiberling. While it will largely remain an office building, he’s exploring a few tweaks—perhaps resurrecting something akin to the former brewery’s legendary hospitality suite, the 33 Room.

Embracing the Vision

“The intent I have is to listen,” Blickenstaff stresses. “I’m not imposing anything.” That begins with preserving the character and vitality, charm and history of the Heights he found so irresistible in the first place while on family visits.

That said, he brings a pair of fresh eyes to a village and a region that do not always see themselves with the same sense of enthusiasm and optimism. “We’re going to preserve what we have, find what we don’t know we have and get that out front, and really get… to be a place that people want to come and live and work again,” Blickenstaff notes.

If that’s music to the ears of the mayor of this community of 6,000—one that lost 20 percent of its population following the closure of the Pabst plant in 1982—well, he can be forgiven. Initially, Mike Phelan was skeptical when one day last May, “a call came in” from “a gentleman from San Diego interested in doing some development in the Heights. “We’re fortunate,” the mayor continued, that “a lot of people” inquire about local residential or commercial development opportunities. “Some we want to partner with. Others we have to do a lot more due diligence.”

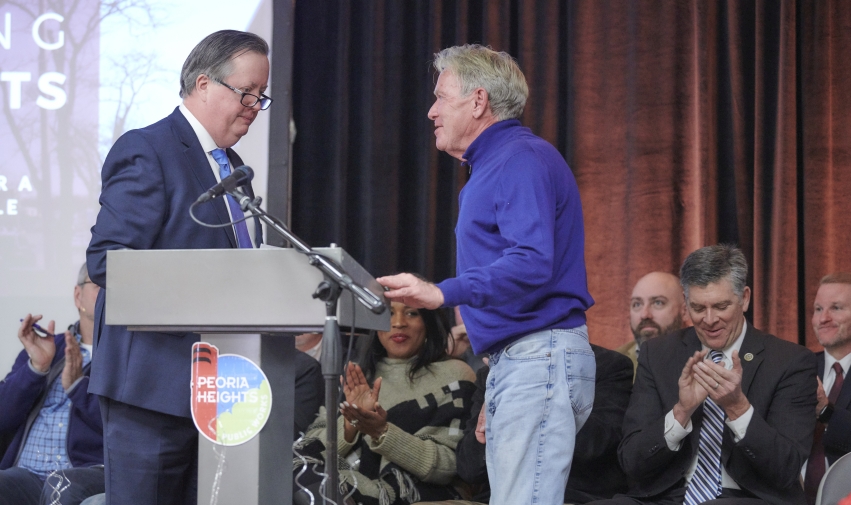

Peoria Heights Mayor Mike Phelan, left, with Kim Blickenstaff at the December 2018 press conference

After at least a half dozen Blickenstaff fly-ins and countless hours of conversation over the last half of 2018, any hesitation the mayor once had has vanished. “He’s really embraced our vision,” Phelan says. He’s proved his commitment with his purchase of multiple properties, including a home in the Heights. He’s using local contractors and labor. He appreciates the critical importance of quality local schools to the health of any community, and trusts his investments can only help in that regard.

“I’m not really a developer,” Blickenstaff admits. “I’m sort of an owner-builder-partner. And I’m not criticizing other people who are developers… There are different ways to do this.”

In the end, he just has a personal connection with this place. If once he left and did not look back for decades, at some point he recognized that the lines of his life, in so many ways, intersect here. Renowned local philanthropist and conservationist Bill Rutherford was his father’s attorney, called the Heights home, and mentored Kim and his brother, teaching the latter to fly on his way to becoming a commercial airline pilot. The Doyle he so admires was Rutherford’s architect. It all started here.

And now he hopes to finish up here, leaving virtually no part of the Heights untouched, from its underutilized riverfront to the top of its bluffs, breathing life into areas that have languished for years.

Blickenstaff has a relaxed, easy-going way about him. He seems to approach all of this with a sense of adventure. Anyone who saw him behind the drums at the Betty Jayne’s inaugural gala could tell he is having fun. But make no mistake: “I’m not a time waster” and “I don’t do things half-assed.”

Sounds like we ain’t seen nothin’ yet. iBi

Visit realizingtheheights.com to follow progress on this series of transformational developments in Peoria Heights.