A group’s decade-long commitment to bringing a children’s museum to Peoria is paying off at last.

There were those who said it couldn’t be done, and after 13 years in the making, Emily Cahill can understand their doubts. But after attending last month’s demolition celebration to mark the beginning of construction on the Peoria PlayHouse, Cahill—a Junior League member and volunteer on the project since its inception—hopes former skeptics are now saying, “Wow, they did it.”

The news spread quickly in June after the Junior League of Peoria (JLP) proudly announced it had met its 90-percent fundraising goal—the target at which construction could commence on the children’s museum, which has already consumed over 100,000 volunteer hours and a half-million Junior League dollars.

Working On a Dream

The dream to build a children’s museum in Peoria started in 2001, when the Junior League took on the project, seeking to fill what it saw as a major gap in the region. Citing the inconvenience of relying on other communities to give their kids interactive learning experiences, dedicated moms described hauling their children to The Magic House in St. Louis, Children’s Discovery Museum in Bloomington and Discovery Depot Museum in Galesburg, as well as to Chicago’s rich campus of institutions. These are all wonderful museums, notes JLP President-elect Colleen DiGiallonardo, but if only there was a similar resource closer to home!

“When I moved here, my kids were little,” she says. “It would’ve been a high point for me if we had had one… And it could really be a great foundation for the community to have something used for recruiting and retaining young professionals—especially those with families.”

“Many of our ladies had seen what these other museums did for their communities and really felt that was something Peoria was missing,” agrees Cahill. “Peoria, today, is still one of the very few communities of our size across the country that doesn’t have a dedicated children’s museum space.”

With this in mind, an original committee of a dozen women began running the idea through the Junior League’s channels—envisioning what such a museum might look like, researching options, determining how many volunteer-hours it would take… and how much money. As ideas for the project solidified, it soon grew larger than anything the organization had done before. Despite these challenges, Cahill declares, “We weren’t daunted.”

Delegations were sent to other children’s museums to gather information, take pictures and build contacts. In addition, the JLP joined the Association of Children’s Museums (ACM), which proved to be a valuable resource on exhibition design and theory, as well as offering a national directory of designers, education consultants and museums—both existing ones and those in the planning stages.

“We found out just how many children’s museums around the country have a Junior League connection,” Cahill says. “Ladies just like us had done this in other communities. That really helped to spur us on and know that this was possible.”

Many Women, Many Hats

Established in 1936 with nearly 450 women from a range of backgrounds, the Junior League of Peoria maintains its founding vision to “bring people together to improve the quality of life in the region” through three main goals: promoting volunteerism, developing the potential of women, and improving communities through the action of trained volunteers. About 20 percent of the League’s currently active members are devoted to the PlayHouse project, while other pursuits continue in parallel, explains DiGiallonardo, who says the organization is experiencing a membership surge, with over three-dozen new members joining the league’s 100 active members and 300 sustaining members so far this year.

Ironically, while the PlayHouse fits the JLP’s bill as an educational, community-based project guaranteed to make a huge impact on the lives of local residents, one of the greatest challenges faced by the original committee was the Junior League itself. The organization’s projects typically adhere to annual timelines, so members can move around on committees and through positions to gain a variety of experience in their volunteer work. This serves the organization well as it develops well-rounded volunteers, well-versed in many different roles. For a long-term project like the Peoria PlayHouse, however, it creates a substantial challenge as volunteers come and go, often with varying levels of drive. For the most part, the women who first launched the Playhouse concept with undying enthusiasm are now less active, sustaining members—having given five years of service.

“Our active membership looks very different than it did when we started this process,” Cahill says with a laugh. “It’s been a challenge to continue to educate our members as to why this is important, because they weren’t the ones who voted in 2001 for us to take this on. But they’re here, still fighting the fight and working on a daily basis to get it done.”

The dependence on volunteers adds another challenging dimension to such a large-scale project. The group’s members come from various walks of life, and many also have children; Cahill herself is a mom to three and works as assistant to the director at the Peoria Park District. “When we started this project, we had no idea that things like September 11th were going to happen, or the economic challenges that have faced our nation over the last several years. This made fundraising more difficult—and we are all volunteers. But we worked together to put out requests for proposals, for exhibit designers, and we interviewed and selected architects. We did all of that as volunteers.”

That includes making the tough decision not to compromise the original dream. Surprisingly, the group’s plans today are identical to what was originally conceptualized a decade ago. “There were several points along the path [where] we could’ve said… ‘We need to lose this exhibit or we want to make this cheaper’… but we didn’t do that,” explains Cahill. “It took a commitment on our organization’s part to say, ‘This is the right thing to do.’”

Foundational Blueprints

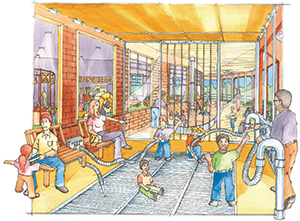

The plans the group is so committed to are thorough, featuring six exhibits grounded in the Illinois Early Learning Standards—the basic curriculum every child in the state must master from preschool through third grade. The JLP has been working closely with Bradley University and the Regional Office of Education to ensure that all activities planned for the museum are tied to what the kids should be learning in the classroom. But the team has even larger goals for the overall design.

“A lot of kids are successful sitting in a classroom with a book or laptop, but just as many need to learn using other methods, [like] their senses of hearing or touch,” says DiGiallonardo. “We’re trying to support what goes on in the classroom… so teachers could introduce a lesson in the classroom, visit the children’s museum to reinforce skills they’re trying to teach their kids, then go back to the classroom and… solidify those lessons.”

As the team gathered research, they were struck by one discovery in particular: 85 percent of a child’s brain develops by the time they are three years old. “If you think about the way our education system is set up… three years old is about the time you send your child off to preschool,” Cahill notes. “It’s absolutely critical that we provide the right sort of environment for children and families to interact with each other, spend quality time and learn together so they have the best possible chance of being successful when they’re ready to enter preschool.” This kind of educational foundation, she adds, carries on for a lifetime.

“The Playhouse is hands-on, interactive learning—so it is actually having people get down to the level of the kids and play with them,” DiGiallonardo stresses. “That interactive portion will help families… Families that play together, stay together.”

A City Centerpiece

A City Centerpiece

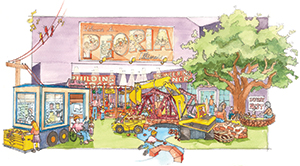

Part of the museum’s charm is based on its location at the Glen Oak Pavilion—the historic, architectural centerpiece of Glen Oak Park in the heart of the city. But the choice of location extends beyond its charisma and natural beauty. In fact, it was the first decision made—to ensure the museum would be in the right place for the goals it intends to achieve.

“We certainly could have put [it] on the north side… or even downtown, but we felt it was absolutely important for us to be in Glen Oak Park because that makes us accessible to a lot more families in our community,” says Cahill. “We conducted a Park District survey… that found more than half of the kids who live in certain zip codes in Peoria have never been more than three miles from their home. If we put a children’s museum out at Grand Prairie, you might as well put it on the moon for those kids—because they’re not going to be able to get there.”

The JLP is working with numerous entities in the community to provide training for local teachers prior to the museum opening next year; all who participate can bring their classrooms through the museum at no charge. It’s also looking into the option of offering a museum membership available for checkout at local libraries to provide access to interested families with a library card. Corporate donors may also sponsor buy-one-get-one-free days or other discounted rates to increase accessibility for their clientele.

Three’s a Team

By collaborating with the Peoria Zoological Society and Peoria Park District, the JLP knew it would be better positioned to leverage the 200,000+ people who visit the zoo each year. In 2011, the three organizations jumpstarted their relationship through the Power of Play campaign, a joint effort that boosted fundraising efforts and will continue to be a critical partnership in sustaining the museum after it opens.

Combined with the expanded Peoria Zoo and Luthy Botanical Garden, the Peoria PlayHouse will offer a day-long destination for children and their families, with ongoing collaboration among the three entities in the creation of programming. The partnership could even become a national model for its savvy approach of joining attractions to programs. “We spend a lot of time in the car going from thing to thing,” says Cahill. “Here, you’ll be able to park once and spend the whole day in a really quality way with your family.”

The JLP has also made a point to approach the Peoria Riverfront Museum not as competition, but as a complement to its goals. The job of a children’s museum is to focus on the community’s youngest learners, Cahill explains. “But we know that if people are regular children’s museum-goers, it fosters in them a better understanding of arts and culture as they move through life, and they more often visit other kinds of museums.”

The JLP stresses the synergistic potential of “growing” museum-goers who will support the Riverfront Museum, as well as other arts and cultural activities in the community, when they’re older. “Together we can provide… experiences that will make our children and families more successful when it comes to literacy, or valuing education, arts and culture in our community. That can only make us stronger.”

A Community Asset

Having now reached 100 percent of its fundraising goal, work on the new Peoria Playhouse got started in July. As it progresses, the JLP will also host a ribbon cutting for Rotary Adventure Grove, a play area located between the children’s museum and the zoo that will serve as a natural connector between the two.

Last May, a handful of JLP members, including Cahill, headed to Virginia to meet with fabricators constructing items for the museum’s exhibits. “We got a piece of tree bark and some leaves that are samples of what the tree is going to be like when you walk in the front door… It was just mind-boggling to see the real thing!” she exclaims. “We’ve reached the point where all those things that were on paper, we’re now starting to see in reality. This is the time when we hope everyone gets excited and helps us finish this.”

If all goes according to plan, the museum will open its doors early next summer. Once up and running, JLP members will have an ongoing presence as volunteers, as well as serving on an advisory committee to provide oversight and strategic direction. Then, it’s about moving forward.

While working to complete the Peoria PlayHouse, the JLP has juggled numerous other projects, including its Kids in the Kitchen program, which encourages healthy eating and lifestyles for children, as well as fundraising and advocacy efforts. The organization has also been absorbed in determining the next large project it will take on after the PlayHouse opens—a formidable task in and of itself. The research process will extend into next year, offering members exposure to each of five potential long-term projects—community gardens, improving female high-school graduation rates in Peoria, raising awareness of the dangers of lead exposure, creating a new foster and abridgement program for young adults, or exploring new advocacy opportunities—before voting on which mission to adopt next.

“We have this parallel in progress so that when the children’s museum requires a smaller amount of our effort, we can make a large impact on the community in a different way,” DiGiallonardo explains. Whatever that next project is, there’s no doubt these ladies will get it done. iBi

To keep up with progress on the Peoria PlayHouse, visit peoriaplayhouse.org.