Illinois’ central location and large reserves make it the eighth largest producer of coal in the nation. Coal underlies some 37,000 square miles of the state—about 65 percent of its surface—and has played a significant role in the history of Peoria-area industry.

Reminders of Peoria’s rich coal mining heritage are in plain sight throughout central Illinois, but deep underground lies the rest of the story: tunnels and rooms, timbers and rails, mine cars, lighting and conveyor systems, and occasionally, the remains of an unfortunate miner, trapped and unrecovered after a collapse.

The availability of natural gas and cleaner-burning coal; labor issues, including strikes, causing unreliable supply; the 1970 Clean Air Act; and the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 all contributed to the shift away from coal. But anyone living in Peoria through the 1950s benefited from the heat, light and jobs generated by this local source of energy.

A Living Map of Local Coal

The place names resonate: Kingston Mines just downriver from Peoria; Orchard Mines, an unincorporated area opposite the bridge near Pekin; Coal Miners’ Park in Pekin; and Mine Hollow Road off Kickapoo Creek Road. Other streets commemorate the mines and their owners: Mohn, Collier, Treasure and Winters in Bartonville. Companies that supplied blasting powder to mining operations named the roads heading into local hollows: DuPont Lane in East Peoria, Powder Mill Road in Edwards, and just down the road, the unincorporated community of Olin, named for a company that made explosives.

From the earliest days, the Illinois River provided an avenue for shipping coal. Traveling upriver in 1673, Father Marquette and Louis Joliet noted coal outcroppings near Peoria. In 1723, Phillipe Francois Renault obtained property rights via a grant from the French Crown for land along the river and back “five leagues” (about 15 miles) on a stream believed to be Kickapoo Creek. Renault, a mining engineer, had a smelter in the St. Louis area and realized that the Kickapoo Valley was rich in coal. A coal outcropping can still be seen as Interstate 474 climbs the hill from Bartonville on the way to Peoria’s airport.

From the earliest days, the Illinois River provided an avenue for shipping coal. Traveling upriver in 1673, Father Marquette and Louis Joliet noted coal outcroppings near Peoria. In 1723, Phillipe Francois Renault obtained property rights via a grant from the French Crown for land along the river and back “five leagues” (about 15 miles) on a stream believed to be Kickapoo Creek. Renault, a mining engineer, had a smelter in the St. Louis area and realized that the Kickapoo Valley was rich in coal. A coal outcropping can still be seen as Interstate 474 climbs the hill from Bartonville on the way to Peoria’s airport.

Prior to the Civil War, Samuel Potts was a prominent mine owner, for whom Pottstown is named. That town and the Kickapoo Valley became the setting for the 1935 book, Horse Shoe Bottoms by Tom Tippett, which narrates the hard lives of the miners and their families, as well as the beginnings of the labor movement among the miners. Neither the town nor the big city that is Peoria is named in the book, but Rocky Glen and Horse Shoe Bottoms along the Kickapoo and familiar names among the Pottstown Cemetery tombstones confirm the author’s roots. Local author Bill Knight reissued the book in 2009.

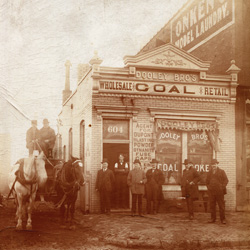

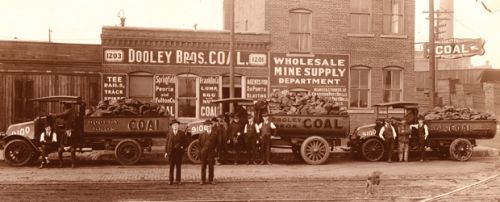

By 1935, the secretary of the Fuel Merchants Association of Peoria noted that the coal industry furnished the livelihood of one out of 10 families in the Peoria District. The 1934 Coal Report showed 89 operating mines in “those parts of Peoria and Tazewell counties adjacent to the city,” employing 2,387 union miners, plus owners, superintendents, maintenance men, truckers and office employees. City directories of the era showed 55 dealers or individuals as retail coal merchants. An estimated 900 to 1,000 independent trucks hauled coal to homes, schools, stores and industrial plants during Peoria’s coal peak.

Dangers of the Job

Mining is inherently dangerous, with cave-ins, explosions, asphyxiations and fires particularly hazardous. Tragedies touched most families, but none on the scale of the 1909 Cherry Mine disaster in Bureau County, where 256 miners perished. An explosion in the Crescent Coal mine along Lamarsh Creek in January 1913 left three dead. Between 1881 and 1954, some 8,441 fatalities occurred in the State of Illinois, according to the 1954 Coal Report.

But not all the deaths occurred in the underground mines. On June 6, 1894, a bloody riot at the Little Mine south of Wesley City resulted in two killed, several wounded and four sent to prison in Joliet. In a similar incident, six miners died and 150 were injured—more than 30 seriously—when a train carrying 200 to work in the Crescent Mines near Hollis derailed on February 20, 1929. Four coaches plunged down an embankment and caught fire.

Powder mill explosions throughout the years not only killed workers, but rattled windows and cracked plaster for miles around. The dangers of the job and increase of riots and strikes led to a decrease in coal mining throughout the region.  The Slow Decline

The Slow Decline

In the 1940s, it was said that a miner could travel via tunnel from Hanna City to all the way to Glasford. A 1940 photo essay on Crescent Mine No. Six depicted mine cars down at an average 150 feet underground, where it took 20 minutes to reach the farthest destination. Although considered a mechanized mine, it used some 45 mules—none more than 52 inches high—on the 15 miles of track in that mine.

By 1973, however, the owner of the Ritschel Coal Company estimated that just 8,000 to 10,000 tons of coal was being delivered to Peoria homes, compared to a peak of 250,000 tons a year. Today, some older homes still have their coal chutes—generally next to the driveway, where the coal was delivered. But the conversion from coal to gas meant the end of coal rooms and clinkers (the ash and partially fused residue from a coal-fired furnace)—and the need for serious spring cleaning!

Reading History in Layers

One of the most accessible former mining sites is at Wildlife Prairie State Park near Edwards. There, a geology professor from Illinois Central College has begun leading field trips for students and adult learners, pointing out the cuts that expose the blue clay, slate, shale and coal layers and the lakes formed after strip-mining operations. Numerous former strip mines have become recreational properties for such groups as the Keystone Anglers and the Hiram Walker Rod & Gun Club. Another former strip mine now serves as the Peoria City/County Landfill.

Clara A. Lauterbach Park on Smithville Road in Bartonville includes 10 acres donated by the Mohn family. The Mohn Mine, which operated under various owners dated back to 1919, closed its shafts forever in 1952. At that time, the Greater Peoria Airport Authority purchased all of Mohn’s mineral rights, thus assuring that further mining beneath airport properties would cease. (Cave-ins had become an expensive and dangerous feature of airport runways by the late 1940s.) Another challenge for the airport involved the paving of runways that had previously been covered with shale, the refuse from area mines. Slag hills or “gob” piles were a common feature of the landscape near mines—materials later used for fill or road grading.

The Illinois State Geological Survey’s Coal Section offers online maps of all recorded mines, but not all area mines were mapped, as was discovered several years ago during the construction of GEM Terrace in East Peoria near the junction of Interstate 74 and Route 116. While placing footings for the building, contractors encountered voids and pulled out mine timbers. Fortunately, mine subsidence insurance is automatic unless waived in local counties, but claims are rare. Property records generally indicate if coal and mineral rights are excepted.

Although coal was forged in pre-historic times, its significant role in Peoria-area history continues to evolve even today. iBi