During the day, Brian Rowe is an engineer at Caterpillar Inc., leading product development for marine engine application software. In the evening, he turns his attention to analog photography, using older, fully mechanical cameras to produce intriguing images quite unlike today’s modern digital snapshots.

Rowe can often be found on the streets of Peoria’s Warehouse District, capturing the soul of its historic buildings, or at concerts documenting live music on film. Peoria Magazine spoke with Rowe about his journey as a photographer and the unique nature of his work.

Tell us a little about yourself, your education and career background.

I grew up in Marion, Indiana, a city of about 30,000, which unfortunately has been hit by the recurring Midwestern theme of closing factories and unemployment. I have a large extended family in northern Indiana, the kind that still gets together for a family reunion at the same city park shelter every year for longer than I have been alive.

When I was young, my family always had a computer around. I used to get magazines when I was a kid that had short game programs written out in the back, which you would type in and save onto cassette tapes. To load the game, you would play the tape back to the computer, which made chomping sounds like a dial-up modem. I always knew I’d be doing something with electronics as a career, so I went to Purdue University to get an electrical engineering degree. Currently I work for Caterpillar, where I lead product development for marine engine application software.

How did you first become interested in photography?

My interest in photography probably started with an Atlas of the Universe book, containing photos from various NASA missions. Before modern image processing, orbiting space probes would take hundreds of photos of a planetary surface, and someone back at NASA would build a mosaic out of them to get a bigger view of the photographed area. I really liked this kind of patchwork photography, so I would go out into the woods behind my house with my dad’s Minolta SRT 101 and take photos of things like overturned trees, and piece them together into image collages.

I did very little photography for several years after that due to the demands of engineering school—and a lack of having my own real camera. During those years, I got into watching classic films from directors such as Jean-Luc Godard and F. W. Murnau, where the style of the image had as much to do with emoting feeling as the story the actors were trying to tell. The camerawork in these films really was an education on framing, location and the importance of telling a story with an image.

What makes your work different from most photographers? Tell us about some of the unique tools and techniques you use.

For my personal art photography, I only use film, which I process myself in my kitchen. Not because of any sense of purity, but because I like the feel of using these old, fully mechanical cameras, which have nothing to do with my electronics background. I have a real fondness for cameras with an interesting back story, because it makes me feel some connection to the time period from which they came. In turn, I try to honor the history of that camera when I find ways to use it.

I particularly like pre-WWII cameras because of their craftsmanship and quirks. Early camera development was like a Cambrian explosion with a countless array of makes and models, all having their own slightly different set of features. It’s a rabbit hole trying to find something that has the qualities you are interested in.

One of the cameras I use frequently is a 6x13 cm ICA Polyskop. With its twin lenses it can take stereo photographs, and by sliding the lensboard over so one of the lenses is in the middle of the film frame, it can take 6x12 cm panoramic negatives. Originally it used glass plates to record the image, but it was modified by someone long ago to take 120 roll film, which is still available from several places online. With the help of one of my friends, we modified it further to include spring-loaded film holders to make it even more convenient to use.

What are your favorite subjects to shoot? Why?

Some of my favorite subjects to shoot are buildings which seem to come out of another time—at night. When I first moved to Peoria, the Warehouse District seemed so abandoned while driving through after dark. It made a big impression on me, and I always wanted to capture the feeling I had looking at these older buildings, which seemed to have some kind of a soul left inside of them. Now that the area is getting a second look from developers, I feel like we need to document what the area was like before things are changed forever.

My other favorite subject to shoot is live music, which on film can be incredibly difficult. You only have 36 shots on a roll of 35mm film, and getting the exposure, focus and composition right can leave you with only a handful of worthwhile images from a couple rolls of film.

Describe some of your favorite pieces and/or more experimental work.

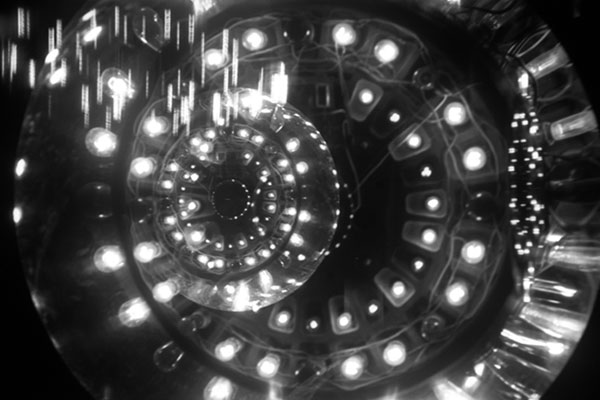

I enjoy creating images that make the viewer wonder how it was done—which can’t be done using a standard digital camera alone. My ultimate desire is to find a way to combine the experimentation with light and technique practiced by the Bauhaus photographers with the documentary style of the Farm Security Administration photographers such as Walker Evans.

One technique I like to use is what’s called a “PENorama,” which refers to a sequence of images taken from left to right with an Olympus Pen half-frame camera. After developing the film, these images can form a diptych, triptych or a sequence of even more images, which you can then print in the darkroom all at once, to provide a kind of panoramic image.

My favorite pieces are the works that, when I return to them, I feel like I have successfully conveyed what it was about that location that intrigued me in the first place. Sometimes I return to locations multiple times in an attempt to evoke the emotion I feel at that place.

Anything else you’d like to add?

I’m always looking for ways to gain access to older buildings. If a building is being rehabbed, I think it’s important that we document what it once was before a new use is found for it. As development in Peoria heats up, more and more of these unique places are disappearing and will never be the same again. I’d love to hear from anyone who has or knows a place that needs to be photographed. PM

To learn more about Brian Rowe’s photography, visit argentography.com. Email him at brian@argentography.com.

- Log in to post comments