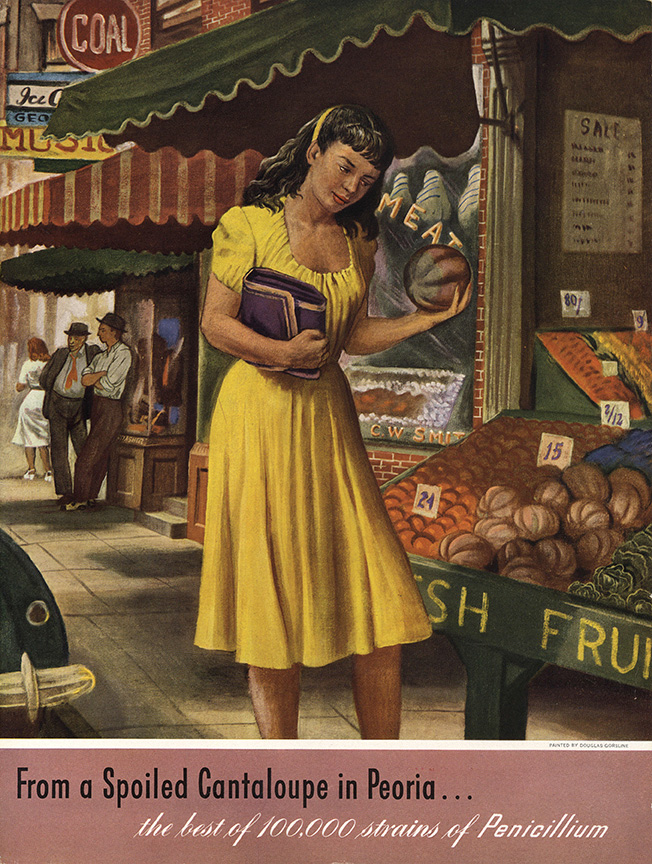

A development pioneered in Peoria, Illinois has saved millions of lives worldwide over the last 75 years: the mass production of penicillin. Given Peoria’s near-celebrity status as the location where a method to mass-produce penicillin was pioneered during World War II, you have probably heard about it at some point. Some also may have heard the story of “Moldy Mary”—an employee of Peoria’s USDA Northern Regional Research Laboratory (NRRL), now referred to as the National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research (NCAUR)—who found a cantaloupe which happened to have a variety of mold containing penicillin growing on it that was especially conducive to mass production.

Fewer may have heard a different story: that the discoverer of said cantaloupe was not an employee, but an unknown Peoria housewife who dropped off the cantaloupe at the lab, never knowing her contribution to the development of penicillin. What most probably do not know is that the exact origin of this strain—the ancestor to the penicillin still in use today—is somewhat controversial. In fact, many aspects about it are still a mystery.

Searching for “Moldy Mary”

When I set out to write about an influential woman from Peoria’s past, I immediately thought of Mary Kay Steven (nee Hunt). Over the years, I have come across articles discussing Mary’s contributions to the mass production of penicillin—especially concerning her find, in a Peoria market, of a cantaloupe with such unique properties. I assumed choosing her as a subject was unimpeachable, given the pride Peoria has placed in its contribution to science through the work done at the NRRL during the war years. That’s when things started to get complicated.

In my position at the Peoria Public Library, it is essential that I provide as much factual information to the public as possible. To that end, I was not satisfied with what I gleaned about Mary Hunt from a few decades-old newspaper articles. My next source was a scrapbook compiled by library staff about the NRRL. It contains many clippings about the work on penicillin in Peoria, but they were inconclusive as to who actually found the cantaloupe. My next step was to contact current NCAUR employees who are familiar with the history of the lab and penicillin production. Informed that I wanted to write about Mary Hunt, they showed some concern because even in scientific circles and within the USDA itself, the information about her role is murky.

Mary herself never doubted the role she had played and gave several interviews over the years in which she discussed finding the cantaloupe, even describing that moment in detail. The supervisors who oversaw her work, however, have given contradictory information over the decades about Mary’s role in the penicillin work at the lab. For example, one supervisor, Robert D. Coghill, veered from giving her credit for the find in publications from the 1940s through the 1960s, to referring to her as “a simple messenger girl” in the ’70s and ’80s. In a 1976 interview he is quoted as saying:

“Actually Moldy Mary was made by the newspapers. The merchants downtown named her… When you think of the tremendous value penicillin has had, there are much more important things to write about than Moldy Mary.”

These contradictions inspired me to find out more about this so-called messenger girl. In the process, I pieced together a loose biographical sketch.

Tracking the Evidence

Mary Hunt, as I discovered through records, was most likely born in 1910 as Marya Hnatusko. She immigrated to the United States in 1913 with her Eastern European family and grew up in the Chicago area. I could not find records between 1920 and 1943 that were a match for a Marya Hnatusko or a Mary Hunt. During those years, Mary said in interviews that she attended the University of Chicago and University of Illinois Medical School, where she studied bacteriology and public health. She also shared in news articles that she had training in the field of nursing and had worked at St. Francis Hospital in Peoria before working at the NRRL.

All of this information calls into question the comment that Mary Hunt was merely a “messenger girl.” I have concluded there was more to her role—especially after reviewing a 1944 publication, Natural Variation and Penicillin Production in Penicillium notatum and Allied Species, written by supervisors of the NRRL penicillin team, who single her out for credit: “We are likewise indebted to Miss Mary K. Hunt for collecting samples of moldy materials and for assisting in the isolation and preliminary testing of many strains.” Robert D. Coghill was one of those authors—and the same supervisor who would later dismiss Mary Hunt’s contributions.

There is a Mary Hunt listed in the 1943 Peoria City Directory as working as a bacteriologist; however, the NCAUR staff I spoke to who work at the lab today believe that title and position may not have been the one she held at the NRRL. This also begged the question: How common was it for a woman to be working as a bacteriologist in the 1940s? That answer is provided in a 1948 U.S. government publication, The Outlook for Women in the Biological Sciences. According to that document, approximately 130 women were employed as bacteriologists in government work before the war, with no substantial increase until the later war years. Therefore, if Mary Hunt was a female bacteriologist with the USDA, she would have had few peers.

The NCAUR supplied me with photographs that show several young women working in the Peoria NRRL laboratories, including one believed to be Mary Hunt. The Outlook for Women publication attributes the choice of women for positions as bacteriologists to their special talents, patience in repetitive work, attention to detail and extensive data-keeping abilities. Information about hiring practices and those employed at the NRRL is not available, so we may never know for sure how many women were employed as bacteriologists at Peoria’s NRRL, nor if Mary Hunt held that exact position.

A Source of Pride

Before writing this article, I spent many hours collecting information from various sources about the development of penicillin and Mary Hunt. Nothing I discovered has helped to prove conclusively that Mary Hunt is the famed “Moldy Mary,” nor do I have conclusive evidence that she is not. But there is no question that Mary was respected for her work, based upon the acknowledgment from 1944 which affirms that she: 1) had the ability to select specimens containing the strains of mold the NRRL sought to investigate further, and 2) that she was skilled at isolating the strains in the laboratory.

Further evidence for Mary’s role can be found in a somewhat obscure article from a scientific journal, written by Milton Scoutaris in 1996. He was the son of Peoria shopkeeper John Scoutaris, who owned a business at 533 Main Street called the Illinois Fruit and Vegetable Company. Milton’s article describes how his father shared the story with his family of the occasion during the war when a customer, Mary Hunt, noticed him removing a moldy grapefruit from display and asked if he could in the future set aside moldy items for her to pick up on a regular basis. He reluctantly agreed—not wanting her or others to think that he kept a lot of spoiled product. But he knew that Mary was involved in war work, so he did not ask too many questions.

At some point, Mary told him it would no longer be necessary to save moldy fruit and vegetables for her, but did not explain why. Several years later, Mary came by the shop again to inform John Scoutaris that “the cantaloupe you provided… is the source of penicillin.” This account became a source of pride in the Scoutaris family and a story they shared many times over the years.

No Insignificant Roles

When I was completing my history degree, I took a class devoted to the study of World War II. One assignment was to conduct an interview with someone who had participated in the war effort. I chose my uncle, who had served in Africa in the U.S. Army Air Forces in a maintenance role. I almost apologetically explained my choice to my professor, thinking I should have interviewed someone who had accomplished something more significant. He explained that there were no insignificant roles—that every participant was needed to further the end objective, the successful conclusion of the war for America.

Likewise, Mary Hunt and her female peers all added significantly to the war work being accomplished at the Northern Regional Research Laboratory. We may never know the specifics of her work or of the other technicians behind the scenes, but there is no question that all of them were indispensible in the development of the mass production of penicillin.

Mary Hunt Steven died on February 22, 1991 in Sedona, Arizona. Her death certificate lists her occupation as a naturopathic physician, but it also indicates she didn’t have an education beyond the 12th grade. Of course, that information could have been omitted. I could find nothing showing that she did (or did not) have the degrees she claimed. However, I was able to track down her “adopted nephew,” who shared that Mary had a practice in her home in Brookfield, Illinois for many years. In fact, he says that she saved his life when no one else could provide a cure for a childhood illness. He also said she had many loyal patients and that she established an office in Sedona after her move there.

Regardless of the mysteries still surrounding Mary and her famous moldy melon, I do believe she was much more than a simple messenger girl. She undoubtedly played an important role at Peoria’s USDA lab as it fought against time to supply the Allies with a wonder drug that would save thousands of lives on battlefields around the world. PM

Chris Farris is reference assistant librarian at the Peoria Public Library Local History and Genealogy Department.

- Log in to post comments