Finding the Right Work/Art Balance

Many artists — and I am using that term broadly to refer to all performing and visual artists — are financially unable to devote all their working hours to practicing their art.

Some use their artistic skills to teach others or to market others’ products, and some — like me — work in fields completely unrelated to their art. In short, they must balance their art with other work.

released on December 14, 2021.

Of course, the notion of balance is relevant to full-time artists, too, and in a more general sense to people outside the arts, especially those who bring a creative spirit to their work.

I believe there are at least three balances that, if carefully monitored, can help artists and other creatives function at higher levels and interface better with the world around them.

COMFORT AND CHALLENGE

We often hear that we need to “step out of our comfort zone” to grow. I think this concept is true, to a point. If we constantly stay in familiar territory, we risk stagnation.

And sure, if we experiment with new styles, tools or media, or if we strive for higher skill levels, obviously we can grow. But we can also grow when our perspectives on familiar territory evolve. As a musician, maybe you glean new meaning from the melody or lyric of a song you have been performing for years, and a new freshness emerges. That’s growth.

Returning to the core issue of balance, if we challenge ourselves too frequently, we risk becoming hardened or even strident — a cold practitioner of self-discipline. Our work may lose its emotional impact and become merely technically impressive. Similarly, if we wallow in our well-worn spaces too much of the time, we risk eroding our artistic essence — the sense of exploration that is core to creative endeavor — and we collapse into self-indulgence.

HEART AND MIND

Building on the contrast of indulgence and discipline, we also balance emotion and intellect, or the visceral and the cerebral. While it is true that music theory is inherently mathematical — and that musical and mathematical aptitude commonly coexist in people — most of us don’t want music to sound like math. We want music to soothe, energize, or at least entertain us.

And yet, if it is too simplistic or too obvious in its attempts to play our heart strings, we might dismiss it. Complexity and subtlety bring intrigue; they can evoke mystery and anticipation, sometimes even wonder. They keep us interested while we wait for the next wallop to our emotions.

A side note: We generally form these reactions to music with great speed and passivity. We don’t pick our favorite music, it picks us. If you don’t believe me, try picking your favorite song on a new album using only the song titles. You are likely to change your pick after you listen, and you may come away feeling as if your favorite song happened to you rather than you picking it.

FREEDOM AND RESPONSIBILITY

Now for the big kahuna, the mother of all balances — and maybe a more fundamental way of thinking about the first two. Freedom and responsibility must stay in balance.

If we have more freedom than responsibility, we risk slowly disintegrating into a self-indulgent or even self-destructive mess. The visual evidence of this problem can get pretty twisted. Imagine a trust fund 20-something pretending to be homeless (yes, unfortunately I’ve seen that).

On the other end of the spectrum, if we have more responsibility than freedom, we risk becoming deeply bitter and cynical, or perhaps feeling trapped in our own lives, all of which, again, can lead to self-destructive behavior.

On a practical level, this balance translates nicely to our artistic choices and how others react to them. If you take no responsibility for trying to soothe, energize, or at least entertain people, don’t be surprised if they lose interest in your work. But if you meet them halfway — for instance, by occasionally playing a more accessible or familiar song — they will give you more leeway to try out your new, original work on them.

In conclusion, how does one manage these balances?

Above all, by living with attention and intention. Be self-reflective and self-analytical, and be honest about it. See what a close friend thinks about your observations. And commit to achievable paths without beating yourself up too hard when you stray from them.

Besides, there might be some cool stuff over there.

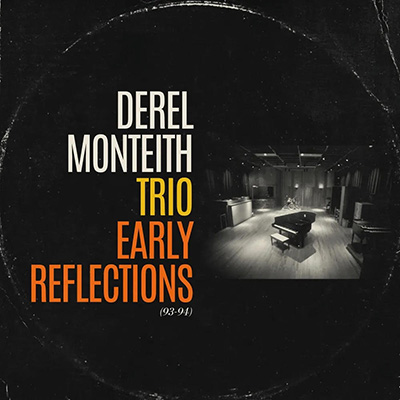

Derel Monteith is an intellectual property attorney at Caterpillar who went to music school before he went to law school. He is an accomplished jazz pianist and composer whose Derel Monteith Trio is a familiar presence on the central Illinois stage. The group’s latest release is called “Early Reflections.”