New in Town: Japanese American Resettlement During WWII

Former incarcerees came to Peoria with their families to pursue new opportunities and remake their lives.

December 7, 1941, “a day that will live in infamy,” marked more than the beginning of direct American involvement in the wars raging in Europe and the Asia-Pacific—it launched an interlude of government persecution of U.S. citizens and residents.

Soon after, in February 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt signed his infamous Executive Order 9066, which created “military areas” in the western United States and provided for the forced relocation of Japanese immigrants and their American-born children from Washington, Oregon and California to camps further inland—in places such as Poston, Arizona, and Heart Mountain, Wyoming. Despite reports from 1941 showing Japanese Americans to be 94 percent loyal to the U.S., roughly 120,000 Japanese Americans left their homes and farms under the cover of armed guards to travel to concentration camps.

Once placed in a camp, individuals had limited options to leave its barbed-wire fences. Incarcerees could enlist in the military, find a work sponsor further east through the government’s War Relocation Authority (WRA), or simply wait for the war to end in hopes of returning to the West Coast. Many young men chose the first option, joining the highly decorated 442nd Regimental Combat Team in Europe, while a sizeable number of incarcerees moved eastward to pursue new employment and educational opportunities.

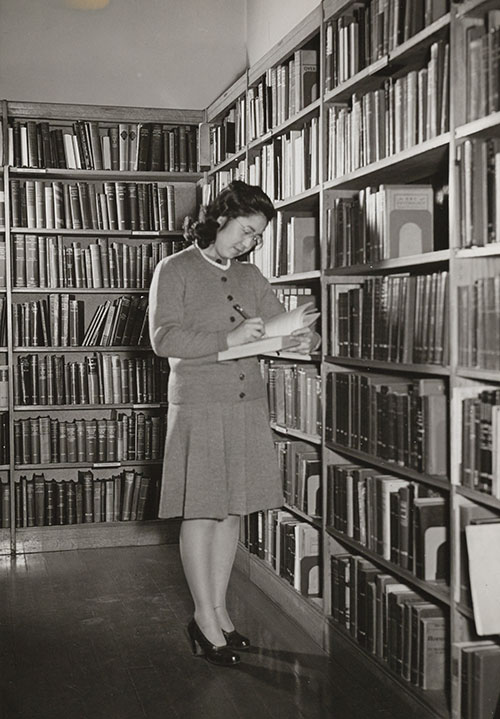

lrene Eiko Yonemura found work at the Peoria Public Library after coming to Peoria in the summer of 1943.

Connections in the Midwest

The WRA helped to establish connections for detainees, primarily in the Midwest, where the welcome was warmer for displaced Japanese Americans than in other areas of the country. The agency worked to handle contracts with employers in need of workers and made efforts to improve public attitudes toward resettlers. Moreover, it launched a public relations campaign to attract more Japanese Americans to the area.

News items appeared in Japanese American publications stating that prejudice was less prevalent east of the Missouri River. Eventually, over 25,000 Japanese Americans relocated to the Midwest during the war, with nearly half moving to Illinois. While the bulk of the internees moved to the Chicago area, some also moved to Peoria—lured by new jobs or the opportunity to study at St. Francis Hospital (OSF) or Bradley University.

In 1942 and 1943, more than 40 Japanese American incarcerees moved to Peoria. The vast majority were single individuals who came to both study and work, though eventually other family members would follow. One individual who ventured to Peoria on her own was Eiko (Irene) Yonemura, who left the camp in Poston, Arizona, for a position at the Peoria Public Library.

Moving a whole family was much more of a challenge. The relocation process was quite complicated, as Sallie Yamada related in a 1943 article for The Peoria Star, saying, “...there is a lot of red tape to coming out.” She was referring to the fact that many families were separated again when leaving the camps, as individuals required a sponsor to leave, and then had to live and work in a new location for a specified time before the family could follow. Despite these difficulties, the WRA sought to place the resettlers in jobs that suited them.

Kelly Yamada tests the strength of a newly-ground lens. The optician was glad to be back at his former trade after his forced relocation from California.

New Opportunities in Peoria

This proved to be the case for Fred Kataoka. Before World War II, he had worked in Fresno, California, as a watchmaker. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, Fred, his wife Alice and their child were sent to a concentration camp in Jerome, Arkansas. When given the opportunity to resettle further east, Fred and Alice jumped at the chance, taking their eight-year-old-son Dickie with them to their new home in the Peoria area, where Fred had the chance to study horology, or watchmaking, at Bradley University. The Kataokas’ positive experience in Peoria and at Bradley soon had them welcoming Fred’s brother Arthur and his family to central Illinois as well.

Like Fred, Arthur Kataoka had lived in California before the war. He married Grace Yochie Nakatani in the late 1930s, and the newlyweds owned and managed an outdoor produce market in Pasadena, California. After Pearl Harbor, circumstances changed dramatically. When the exclusion of persons of Japanese ancestry began in larger cities along the West Coast, Arthur closed his business and headed with his family to Del Rey, California, where his wife’s family lived. They hoped to avoid moving further east. The move, however, only served to postpone the inevitable, as the family soon had to board boxcars taking them to a concentration camp in Gila River, Arizona.

Eventually with the assistance of the War Relocation Authority, Arthur Kataoka secured a sponsor in Minnesota and left to work on a farm there. He routed his trip through Peoria in order to visit his brother, who was by then attending Bradley University. That simple decision would set the course of destiny for his future generations.

Arthur arrived on a frigid February day, and thought he had reached the “end of the world.” Despite the erstwhile Californian’s reaction to the harsh Midwestern winter climate, it was on that visit that Arthur decided to stay and settle in Peoria near his brother, rather than carry on to Minnesota. He acquired a job as a baker at Bishop’s Cafeteria and was glad to work somewhere warm, away from the freezing weather. Arthur would later tell his children that forsythia blooms became his favorite in Illinois, because they signaled to him that “life did exist at the end of the world.” Soon after, Arthur’s family joined him in Peoria. Two of Alice’s sisters, Ann and Rose, also came to live with them in their three-room house, and the girls worked as orderlies at St. Francis Hospital.

Peoria afforded the Kataokas a new opportunity that might have been impossible in California following the outbreak of war. When the fighting finally ended, Arthur felt the Midwest would be safer from prejudice than other areas of the country and offer his children more opportunities for success. This finalized his decision to make Peoria his family’s permanent home. As the years passed, the Kataoka family grew and thrived. Grace gave birth to three more children, who all graduated from Manual High School. The family eventually saved enough money to buy their own bakery, King Pie Bakery, which they ran successfully for many years.

The honored American custom of raiding the icebox was especially pleasurable to the Yamadas after life in a relocation center.

Determination and Adaptability

Strong family ties also drew Bert Arata and his family to central Illinois; Alice Kataoka, Fred’s wife, was Bert’s oldest sister. Like the Kataokas, the Aratas had also lived in Fresno, California, prior to the concentration camps in Jerome, Arkansas. In 1942 Bert, his wife Chiyoko, and their two young daughters boarded trains headed east carrying only $100 in cash—all of their other possessions had to be left behind.

During their time in the concentration camp, the small family lived in a one room, dirt-floored barrack. In 1943, Bert received permission to leave the camp to find work in the Midwest, but the rest of the family stayed until 1944, when they were also allowed to leave due to an amnesty policy for American citizens. They followed Bert to a small town in Michigan, where he had a job in a greenhouse.

When the war ended in 1945, the Aratas moved to Peoria to be near their extended family, the Kataokas. Bert entered school at Bradley University to study watchmaking, graduated from the program, and worked at Peoria Jewelry as a watchmaker until his death in 1985. Their family also expanded with the birth of two more children, all of whom attended Peoria Central High School. Daughter Midori (Dori) obtained a degree in education from Bradley University, and taught at a variety of grade schools in the Peoria area, including Harrison and Whittier. She eventually retired as a third-grade teacher and now resides near Springfield in Athens, Illinois. Amidst the challenges presented by their relocation in the 1940s, the Arata family proved their determination and adaptability by remaking their lives in Peoria.

Former incarceree Kelly Yamada also found employment in Peoria following his time in the Poston, Arizona, concentration camp. Having worked in the optical business in Oakland, he was able to secure a position as an optician at Bard Optical in Peoria in April 1943. Kelly became established enough that after three months in the summer of 1943, he sent for the rest of his family members, including wife Sallie, sons Dexter and Terry, and his in-laws.

Mrs. Yamada gave birth to their second son, Dexter, while still in the Poston camp, and their daughter Marcia was born at OSF in Peoria. The medical advances taking place at OSF at that time spared Marcia from the blindness that plagued many premature infants of the era. She would later attend Stanford University and enjoy an illustrious career as a metallurgical engineer. Kelly and Sallie even maintained a close, lifelong friendship with Warren and Jeanne Hoerr, their Peoria neighbors who had welcomed them affectionately to the neighborhood in the 1940s.

Article co-author Tina Morris with Dori (Arata) Kruger, October 2018

A Positive Legacy

The Kataokas, Aratas and Yamadas represent the positive legacy that Peoria and the Japanese American former incarcerees left on one another. Peorians extended welcoming arms, providing educational and employment opportunities at a time when both were unavailable to the former incarcerees in other areas of the country. Beyond professional experiences, all Japanese Americans who moved to Peoria share stories of neighbors and church members who became close friends and advocates for them. But the benefits flowed mutually, as Japanese Americans provided needed services in Peoria due to the demands created by the war.

The individuals and families who came to central Illinois contributed to the area economically and socially. They invested in their new community, and continued to invest in their country as well. Japanese Americans endured trying circumstances during the war, overcame great odds directly after it, and triumphed in the decades following. In the Midwest specifically, Japanese American resettlers showed courage and resilience in choosing new homes and careers, creating brighter futures for themselves and their children.

During World War II, the United States, blinded by fear and racism, forgot its founding as a country of immigrants. But as seen in these cases, the hard work and perseverance of Japanese Americans reminded the country of its values. The people of central Illinois who welcomed the new arrivals into their community also played a part in ending this short interlude of intolerance in America’s long history of strength through diversity. iBi

Rustin Gates is Associate Professor of History at Bradley University and the Peoria lead for the Courage and Compassion exhibition. Returning Bradley student Tina Morris is a history teacher, WW II researcher and mother of six who resides in Germantown Hills, Illinois.