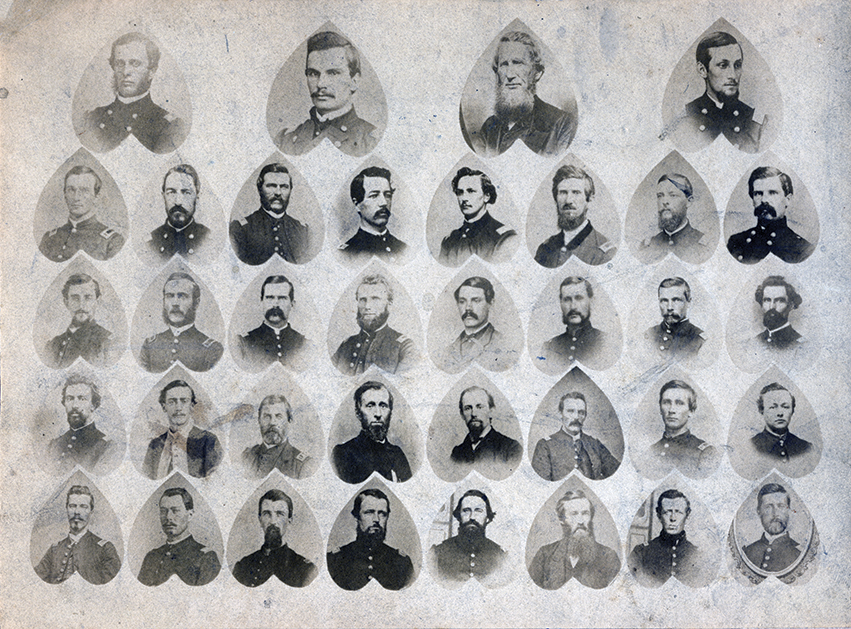

A Condensed History of the Illinois 77th Volunteer Infantry Regiment

Comprised of volunteers primarily from Peoria County, the regiment served from September 1862 through July 1865.

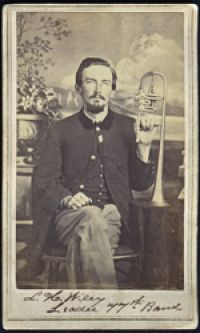

In the second year of the Civil War, not long after the horrific battle fought at Shiloh, President Lincoln issued a call for an additional 300,000 volunteer troops. In Illinois, Governor Yates authorized Charles Ballance, a prominent citizen of Peoria, to raise a regiment of infantry. In total, 882 men were originally recruited for the Illinois 77th Volunteer Infantry Regiment, primarily from Peoria County, including Elmwood (88), Rosefield Township (85), Peoria (70) and Brimfield (42). The volunteers were organized into 10 companies, each commanded by a captain.

First Orders

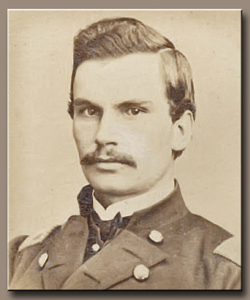

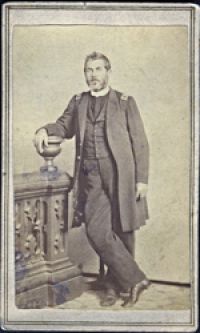

David P. Grier—a native of Elmwood who had previously served with the Missouri Volunteer Infantry and participated in the battles of Fort Henry, Fort Donelson and Shiloh—was appointed colonel to command the new regiment. Grier’s men were provided regulation blue uniforms and the latest Enfield rifles, and trained for a month in Peoria. As they adjusted to camp life, perhaps the most significant challenge they faced was the food they were provided. Though none of the men were experienced cooks, they soon learned they must cook for themselves or starve.

After a month of training at Camp Lyons, on October 4, 1862, Colonel Grier received orders that the regiment was to transport by train to Cincinnati. This came two weeks after the Battle of Antietam—the first major Civil War battle to take place on Union soil and the bloodiest single-day battle in U.S. history, with a combined tally of dead, wounded and missing at 22,717.

After a month of training at Camp Lyons, on October 4, 1862, Colonel Grier received orders that the regiment was to transport by train to Cincinnati. This came two weeks after the Battle of Antietam—the first major Civil War battle to take place on Union soil and the bloodiest single-day battle in U.S. history, with a combined tally of dead, wounded and missing at 22,717.

And so, the young volunteer soldiers from Peoria County initially headed east. After arriving in Cincinnati, they crossed the Ohio River and camped at Covington, Kentucky. Kentucky was one of the pivotal border states; though it had not joined the Confederacy, there was a great deal of support for the rebellion. Over the next month, the men of the 77th marched directly south into the heart of Kentucky, finally arriving at Richmond, Kentucky on November 2nd.

After camping there for a week, the regiment received orders to march back west toward Louisville. Arriving at the Ohio River, the men loaded onto steamboats and headed for Vicksburg, the confederate stronghold on the Mississippi River.

Engaging in Battle

In December, the regiment received its first battle experience as the men engaged in what became known as the Battle of Chickasaw Bayou. A total of 30,000 Union troops under the command of General William T. Sherman attacked the Vicksburg defenses from northeast of the city. The 77th Illinois Regiment was at the front of the lines—so close to rebel lines that they would talk back and forth with the “Johnnies” in the evenings. The Confederate defenders successfully repulsed the attacks.

Now under the command of General John H. McClernard, the men of the 77th embarked on a new mission with renewed vigor and enthusiasm. They boarded river transports and proceeded up the Mississippi River and into the state of Arkansas until they reached a Confederate earthen fort named Fort Hindman. On January 11, 1863, the Union forces attacked and captured the fort, with the 77th again on the frontlines. Members of the regiment later proudly claimed they were the first to scale the fort’s parapets. The 77th suffered six men killed in the battle, with another 39 wounded.

On January 17th, they left Fort Hindman and returned to the Vicksburg campaign, but the next several months were miserable, as the Union forces found themselves camped in a vast sea of mud as the Mississippi River flooded from continual rains. Unusual freezing temperatures added to their sufferings, as the troops grew sick and died by the hundreds.

On April 30th, the troops crossed the Mississippi River and attacked rebel positions at Port Gibson, south of Vicksburg. Throughout the month of May, General Ulysses Grant’s forces continued to engage and drive the Confederate forces back into the city. Finally, on May 22nd, the Union army attacked the Vicksburg defenses. While not successful in capturing the rebel stronghold, Union troops now encircled Vicksburg, and the Confederate garrison was cut off from supply and communications with the outside world. On July 4, 1863, the Confederate forces agreed to an unconditional surrender.

General Grant was eager to seize upon the victory to drive Confederate General Joe Johnston and his rebel army from the state of Mississippi. And so, on July 5th, Union forces—including the Illinois 77th Regiment—began a march to the east toward Jackson. From July 11th through the 16th, Grant’s army engaged the rebels around Jackson, but on the morning of July 17th, they discovered the Confederate forces had retreated during the night. On July 20th, the regiment went to work about 15 miles south of Jackson, destroying a section of railroad line. About two or three miles of rails were placed atop stacked ties, which were set on fire. As the rails began to bend, they were twisted around trees and rendered useless.

General Grant was eager to seize upon the victory to drive Confederate General Joe Johnston and his rebel army from the state of Mississippi. And so, on July 5th, Union forces—including the Illinois 77th Regiment—began a march to the east toward Jackson. From July 11th through the 16th, Grant’s army engaged the rebels around Jackson, but on the morning of July 17th, they discovered the Confederate forces had retreated during the night. On July 20th, the regiment went to work about 15 miles south of Jackson, destroying a section of railroad line. About two or three miles of rails were placed atop stacked ties, which were set on fire. As the rails began to bend, they were twisted around trees and rendered useless.

Ill-Fated Campaigns

After returning to Vicksburg for a well-earned rest, the Illinois 77th found they had been attached to the Department of the Gulf under the leadership of Major General Nathaniel P. Banks. Unfortunately, the department did not have a clear objective; General Banks was more of a politician than a solider, and as a result, the troops wandered somewhat aimlessly through Louisiana and Texas. Colonel Grier, the commanding officer of the Illinois 77th, had been home on furlough. He returned to the regiment, bringing with him a new stand of colors presented by the Women’s Aid Society of Peoria to replace the colors that had been lost at Vicksburg.

By December 17, 1863, the men from Illinois had returned once again to the banks of the Mississippi, where they boarded the steamship De Molay, headed into the Gulf of Mexico and turned west toward Texas. They eventually landed near Matagorda Bay, where they celebrated Christmas by swimming in the Gulf of Mexico.

After nearly two months of inactivity along the Texas coast, the Illinois 77th finally received orders and departed on February 22nd, again on a steamship headed back to the Mississippi River. They would now become part of the ill-fated Red River Campaign, as General Banks marched his troops north through Louisiana toward Shreveport. Union strategists believed control of the Red River would separate Texas—the source of much-needed guns, food and supplies—from the rest of the Confederacy.

On April 8th, the Illinois 77th was near the head of a long column of Union forces not far from Mansfield, Louisiana when they were attacked by rebel soldiers. In the ensuing battle, the wagons of the main supply train blocked the single road the Union forces had advanced upon, thereby preventing Union reinforcements from advancing. In all, the Illinois 77th lost nine men killed, 17 wounded, two missing and 143 taken prisoner.

Damn the Torpedoes

In the summer of 1864, the Illinois 77th Volunteer Infantry Regiment was still reeling from the fiasco of the Red River Campaign. Now they were assigned to a new general, Gordon Granger, who had a specific objective: to attack the forts and Confederate fleet in Mobile Bay, Alabama.

That July, the men of the Illinois 77th Regiment found themselves in camp at Baton Rouge, Louisiana. On July 27th, the men turned over their Enfield muskets, which they had carried for almost two years, and received new Springfield muskets. They boarded another transport, the Saint Charles, and headed down the Mississippi toward Mobile Bay. On August 3rd, the troops were unloaded from the transports on the west end of Dauphin Island at the entrance to Mobile Bay. The rebels controlled a large, brick fort on the eastern end of the island, called Fort Gaines. Three miles away, across the entrance to the bay, was another brick fort, Fort Morgan. The troops under General Granger were to coordinate an attack on these forts with a fleet of gunboats under the command of Admiral David Farragut.

On August 5th, the attack commenced. While General Granger’s land forces attacked Fort Gaines, Admiral Farragut ran his fleet past the guns of Fort Morgan and attacked the Confederate fleet in Mobile Bay. It was during this fight that Farragut uttered perhaps the most famous phrase in naval history: “Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead.” Fort Gaines surrendered after three days of attack, and the Illinois 77th made camp adjacent to the fort. On August 22nd, a concentrated attack commenced on Fort Morgan; it surrendered a day later.

Rest and Release

Two years of military service had taken a heavy toll on the men from central Illinois. They suffered high casualties during battles, and sickness had resulted in even more deaths. The men were extremely fatigued and greatly in need of a period of rest. Fortunately, their commanders recognized this, and the regiment was assigned to duty in New Orleans for the next fall and winter, guarding prisoners of war.

In their spare time, the men took advantage of the social opportunities available in the south’s largest city, including theater and dances. After visits from the paymaster, they were able to supplement their rations with fancy foods and luxury items. They were issued a daily ration of cod fish and could receive packages from home, including such luxuries as butter—something most of the men had not tasted in over two years.

In February 1865, the Illinois 77th headed out of New Orleans as part of a Union force with the objective of driving the Confederate defenders from the city of Mobile and adjacent forts on the east shore of Mobile Bay. During March and April, Union forces steadily advanced on the city, capturing both Spanish forts and Fort Blakely, and taking many rebel prisoners. By April 13th, word reached the Union forces that General Lee had surrendered to General Grant at Appomattox, Virginia four days earlier. The momentous occasion was celebrated with rations of liquor issued to the troops, many of whom took double portions and became gloriously drunk, yelling and howling into the night.

In February 1865, the Illinois 77th headed out of New Orleans as part of a Union force with the objective of driving the Confederate defenders from the city of Mobile and adjacent forts on the east shore of Mobile Bay. During March and April, Union forces steadily advanced on the city, capturing both Spanish forts and Fort Blakely, and taking many rebel prisoners. By April 13th, word reached the Union forces that General Lee had surrendered to General Grant at Appomattox, Virginia four days earlier. The momentous occasion was celebrated with rations of liquor issued to the troops, many of whom took double portions and became gloriously drunk, yelling and howling into the night.

With the war basically over and a Union victory guaranteed, all that remained for the men from central Illinois was their release from service—and a long trip home. On May 4, 1865, the Confederate Department of the Gulf formally surrendered to Union forces at Citronelle, Alabama, and all hostilities were ordered to cease throughout the region. Several days later, the Illinois 77th Regiment, along with other Union forces, entered Mobile. On May 16th, the troops received word that Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederate States of America, had been captured a week earlier in Georgia.

Colonel Grier, who had led the 77th Illinois since it was formed, was promoted to Brevet Brigadier General “for faithful and meritorious services during the campaign against the city of Mobile and its defenses.” Finally, on July 1st, the regiment received word that an order had been issued for the 77th to be released from service.

Civilians Again

The 77th Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment was officially mustered out of service at 1pm on July 10, 1865 at Mobile, Alabama. On July 23rd, the troops arrived at Camp Butler in Springfield, Illinois. After turning in their guns and tents, they were officially mustered out of service to the State of Illinois on July 28th and were once again civilians. They paid their own fares and embarked on a train traveling back to Peoria, arriving on July 29th. They immediately marched up to Rouse Hall at the corner of Main and Jefferson streets, where the Ladies National League had prepared a sumptuous breakfast for them. The regiment finally disbanded, the men went their separate ways to greet their loved ones, from whom they had been separated for so long.

They had volunteered with a tremendous sense of patriotism, eager to serve for the glory of God and country. Over three years, they felt the extreme agony of conflict, saw untold horrors in battles, and experienced disastrous effects from unqualified commanders. Most of them would never again visit the southern states, but the memories of their experience would transform their lives.

Of the original 882 members of the Illinois 77th Volunteer Regiment, 35 men were killed during battle, while another 30 died from wounds suffered during those battles. A total of 110 men died from various diseases; another 189 men were discharged for various reasons; and 34 men were reported to have deserted. Just 424 men—less than half of the original total—were mustered out of service at the end of the war. iBi

Mark L. Johnson is past president of the Peoria Historical Society.