Memoirs of a Unique District

From 1994 to 2008, Ray LaHood represented the 18th Congressional District in the U.S. House of Representatives, where he was known for his efforts to increase civility and forge bipartisanship. Upon his retirement from Congress, he was appointed Secretary of Transportation, serving in President Barack Obama’s cabinet for nearly five years.

As longtime director of the Dirksen Congressional Center in Pekin, Frank H. Mackaman works to help people better understand Congress and its leaders. The Dirksen Center is the repository for the congressional papers of Sen. Everett Dirksen, Rep. Bob Michel and LaHood, among numerous other collections.

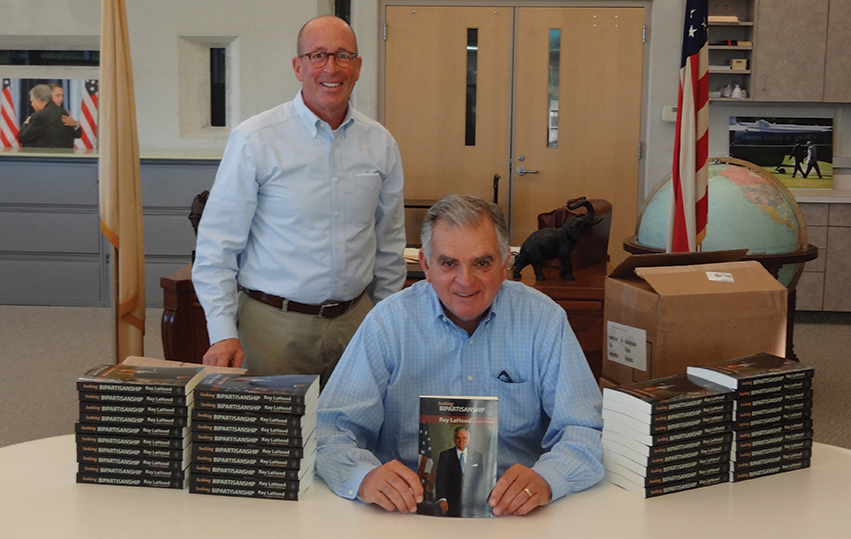

Published in October 2015, Seeking Bipartisanship: My Life in Politics was a collaboration between the two men, a memoir highlighting LaHood’s career in public service and more specifically, his efforts to work across the aisle, with Democrats and Republicans alike. In a time of divisive rhetoric and dysfunction in Washington, its message of civility is more relevant than ever. In this lightly edited conversation, iBi sat down with Mackaman and LaHood to discuss the book, LaHood’s political career, the history and mission of the Dirksen Center, and more.

How did the book come about, and how did it become a collaboration between the two of you?

LaHood: Frank and I had worked together over two or three decades because of his work getting Bob Michel’s papers organized—we made sure all of that was in order—so I really became acquainted with the Dirksen Center. Frank is a very good wordsmith, and he’s written a lot. He and I put together an agreement for my papers… to talk about some of the seminal things that occurred during my 14 years in Congress: the 1994 election, the bipartisan retreats, impeachment, Iraq, 9/11. We came to the idea that we would try to collaborate on a book, and it just evolved over time.

What goes into organizing a congressional collection of papers?

Mackaman: Each one is unique. There is no standard organizational scheme, so Everett Dirksen’s papers are organized completely differently than Bob Michel’s or Ray LaHood’s. One of the challenges in writing the book was that the documentation for the congressional chapters is so much better than the documentation for the DOT [Department of Transportation] chapters. That’s for one simple fact: a member of Congress owns his or her papers. A Cabinet official’s papers are owned by the taxpayer, by the federal government; they end up at the National Archives.

So with regard to the DOT chapters, was it mostly recollection and memory then?

LaHood: We had a pretty good chronology of the issues, and we were really looking at it from the perspective of a Republican in a Democratic administration—issues where the White House would ask me to get involved in helping to try and find votes. Obviously, the stimulus, ObamaCare and the transportation bill… Our view was on the bipartisan nature of all that—how I was used as an integral part of the Obama team on a number of things they were trying to get done.

Mackaman: I think there were three types of books that could be written. There is a history; this is not a history because it does not pretend to be definitive in the research or interpretation. It could have been an autobiography, but it doesn’t deal in depth with… family, genealogy, etc.—those kinds of things are only hinted at in the first chapter. It’s a memoir, so it does rely more on memory—and the interpretation through memory—than a history or an autobiography would.

As you combed through the collection, how did you decide which material to use?

Mackaman: It really occurred in two phases. In the first couple of years, we are just talking about his congressional years. Ray set the general outline; he said these are the five or six events that made my career [in Congress] memorable. My job was to figure out what in his papers helps tell the story. So, Ray’s chairing of the bipartisan civility retreats—outstanding documentation. Future historians can go to his papers and find a wealth of information that we could not include in the book. On the Gingrich revolution and Ray’s frustration with the Republican leadership: again, pretty good documentation. But when you get to 9/11, there is relatively little

[documentation] because of national security—a lot of it is classified and will be for a long time. So those were the challenges. That was phase one.

Once Ray finds out he is going to be appointed to the Cabinet, we have to suspend writing of the book. First, because of the ethics rules: he can’t produce a book while he’s in the Cabinet. And the second reason is [we felt] we now have the final chapters that can make this story even more exceptional. So we suspend work on the book while he’s in office, and resume once he leaves. Then, the challenge is to convert these episodes into some storyline, a theme. That emerged pretty readily: it was bipartisanship, as contrasted with the political environment in Washington.

LaHood: This is a very historic district, once represented by Abraham Lincoln… Then you have Everett Dirksen, who has an extraordinary career. A member of Congress, he gets sick, gets an eye disease and quits Congress, which is unheard of today. He finds a cure for his disease and decides to run for the Senate against the majority leader, Scott Lucas, who lived 50 miles away in Havana! Now, that will never happen again.

So Dirksen not only serves in the House, he serves in the Senate and helps [President] Johnson pass the Civil Rights Act and other major legislation as a conservative Republican from a conservative district with a liberal president. Then you have Bob Michel, who works with all kinds of presidents, but as leader, he worked with Reagan, Bush and Clinton. And you have me for 14 years; I obviously never rose to leadership the way Dirksen and Michel did, but I was involved in a few important matters. And then to be succeeded by Darin [LaHood]—with a little controversy in between—people are going to look back on this district. Unique political figures, during very unique times.

As a Congressman, you were frustrated with the Republican leadership, who kept you from ascending to a leadership role. Then you join a Democratic administration and experience similar frustrations, in terms of Cabinet meetings feeling scripted. Was this part of the motivation in getting your story out?

LaHood: Not really. This book wasn’t written out of being disgruntled about anything; it was more of a reflection of the political realities, some of which I created myself. If I had signed [Newt Gingrich’s] Contract with America, my career would have taken a different course; no question about that. In terms of my ability to rise in leadership, people might have seen me more as a so-called team player. My frustration in the administration was [being kept out of] the inner circle; they were calling the shots. And that’s not unique to Obama’s White House, that’s true in every White House. Reagan had Jim Baker, Ed Meese and Mike Deaver—they ran everything. Nixon had Haldeman. Everybody has a handful of people in the White House who they trust.

With the book’s release last fall, the press focused on your frustrations with the Obama administration. Were they fair in portraying the entire picture?

LaHood: The New York Times article was very accurate—it was very fair. I didn’t particularly like the headline [“Promised Bipartisanship, Obama Adviser Found Disappointment”], but they write headlines to get attention. I’m sure the White House didn’t like the headline. But if they read the book, they would see plenty of criticism against Republicans too, particularly the Tea Party.

Mackaman: The only criticism appeared in an Esquire article, which simply said: if you expect bipartisanship to grow out of a handshake and a dinner party, it’s not going to happen. Your faith is misplaced if you think that’s the solution to the dysfunction in Washington. There is no simple explanation for how we got where we are—or how we get out of this. I think [the book] is a nuanced interpretation. It’s balanced; it’s not bombastic. That’s how Ray approaches everything.

You write that your role in Congress was quite different from your predecessor, who, as minority leader, was more focused on national topics. But he almost lost re-election in 1982—can you talk about that?

LaHood: One of the reasons I was hired in ’82 was because Bob [Michel] did have a close election. His staff felt he needed a bigger district operation; he needed someone on the ground 24/7 looking after the interest of the people... Craig Findley, former state representative from Jacksonville, and I were both hired to really make sure the district was being well served by Bob and his ability to get things done in Washington. So Craig and I opened up offices in Jacksonville and Springfield—two places where Bob didn’t have an office. We spent the next several years working hard, getting involved in the community, and making his presence known. And it worked—he never had a close election after that.

And then you carried that thinking into your own term?

LaHood: I did. I knew I would probably not be in leadership... The only way to get your name on a bill is if you are a committee chair, and that wasn’t going to happen. So I just decided that I wanted to really make a difference in my district. That’s why I wanted to be on the Appropriations Committee. I don’t think that I-74 area would have my name on it if I hadn’t gotten $400 million to make it a safer road. And that was because I was on the Appropriations Committee, and I was paying attention.

Between [Sen. Dick] Durbin, myself and [Rep.] Denny Hastert, we essentially got the seed money to get the Lincoln Library and Museum built in Springfield, and I did that in every part of the district. We also got involved with Habitat for Humanity and with community health clinics… Knowing that I was not going to be a big legislator… and that I was probably not going to be in leadership, I decided to be a leader in my district.

Between [Sen. Dick] Durbin, myself and [Rep.] Denny Hastert, we essentially got the seed money to get the Lincoln Library and Museum built in Springfield, and I did that in every part of the district. We also got involved with Habitat for Humanity and with community health clinics… Knowing that I was not going to be a big legislator… and that I was probably not going to be in leadership, I decided to be a leader in my district.

Did you struggle over the decision not to sign the Contract for America in 1994?

LaHood: Not at all. I knew that when I didn’t sign, people were not going to be happy, but I wasn’t crying in my beer about it. I recognized that’s the way politics works. I’m very proud of the fact that I survived and outstayed Gingrich, [Rep. Dick] Armey and [Rep. Tom] Delay. They were walking out the door with a cloud over their heads; I was still standing there with a rainbow over mine.

So you ended up chairing the Clinton impeachment hearings…

LaHood: When we came into the majority in 1994, not one Republican had ever presided over the House. No one really knew what to do. So a few of us developed a style of fairness: following the rules, allowing members to speak according to their time, not trying to push the House one way or the other. I developed a good style, and Newt recognized that. He had already announced he was not going to stand for Speaker. His infidelities had been disclosed; he knew he couldn’t be up there chairing impeachment… and he told his staff he wanted me to do it. So, in spite of the fact that maybe early on, people didn’t consider me a team player, I think Newt recognized that the best person for the job was someone who had chaired some very controversial debates and kept things under control on the House floor.

There’s a brief period of time when Rep. Bob Livingston is set to become Speaker, then drops out, and someone mentions you as a possible Speaker. Can you talk about that?

LaHood: On the second day [of impeachment hearings], we open up the proceedings at 9am. This is the day we’re going to vote on four articles of impeachment—it’s high drama. Livingston immediately announces he is not going to stand for Speaker… and the air went out of the chamber. People were moaning and groaning and complaining, and Democrats were coming over to Livingston… who was very popular because he chaired the Appropriations Committee. People on both sides of the aisle liked him. I remember [Rep.] Steny Hoyer coming over and talking to him right there at the podium, saying, “You can’t do this. You have to rethink it. Let’s meet.”

So it took everybody by surprise…

LaHood: Yes, everybody. And someone… asked if we should suspend the proceedings. I didn’t check with leadership; I just decided to move ahead. We had to focus on the business of the day, and I think people appreciated that decision.

Then Mel Watt, a Democrat from North Carolina whom I became friends with through our bipartisan retreats, said, “If I can put together enough Democrats with Republicans, would you consider being a candidate for Speaker?” I said that’s not going to happen—I just knew, politically, that couldn’t happen. I knew DeLay was trying to handpick his own person; he couldn’t do it because he was too controversial. Armey was right behind Newt as majority leader, but there was no way DeLay was going to go to Armey because they hated one another. So he picked the guy he felt he could control, Denny Hastert.

…who ended up lasting a very long time in that role.

LaHood: He did. The longest-serving Republican speaker.

What led you to come up with the idea of the civility retreats and the focus on bipartisanship?

LaHood: Rep. David Skaggs of Colorado approached me and asked if I would be willing to cosponsor a bipartisan retreat. We started circulating a petition in order to persuade the leadership—I collected a bunch of Republican names; he collected a bunch of Democratic names. Newt agreed to it immediately, and I think [then-Minority Leader] Dick Gephardt did, too. I thought it was a great idea.

Is it surprising to see how much worse the incivility has gotten in Washington today?

LaHood: It is a little surprising, but I credit most of that to the Tea Party. They have the ability to shut down the government, disrupt the legislative process, and they figured out how to run a speaker out of office. They are pretty much out for themselves; they don’t care much legislating or solving problems.

Today, we are witnessing an unprecedented level of incendiary rhetoric in politics, most prominently with Donald Trump. What will it take for your more moderate brand of Republicanism to prevail over that wing of the party?

LaHood: I think it will take an election—that’s what we’re going through right now. I think the people almost always get it right. They understand the importance of electing people who want to solve problems and get things done. I think these Tea Party people are going to do themselves in by doing nothing. People don’t stand for that for very long. In the end, people want Congress to solve the immigration problem, to fix the complicated tax code, to fix our infrastructure. And if these guys in the House continue to resist, they could get thrown out of the majority. So I do think it’s our election process. I think it’s the American people saying we want leaders who are going to lead.

Did you get flak for agreeing to join a Democratic administration?

LaHood: You know, I really didn’t. Nobody ever said, hey, you’re a traitor. I think when Darin got to be state senator and started traveling around the district, people would ask why his dad was working for Obama. I think he felt people didn’t quite understand why I did it… but no one ever said that to me.

Tell us about your work since leaving the Department of Transportation.

LaHood: I joined DLA Piper, a law firm, and I do consulting with a few transportation companies. I’ve represented Hyundai on some safety matters... Accenture asked me to help with some pipeline safety issues… a few clients like that. I belong to an organization called Building America’s Future. [Former New York Mayor Michael] Bloomberg, former Gov. Ed Rendell of Pennsylvania and I are the three co-chairs, and we travel around the country promoting transportation infrastructure. There’s no pay, but it’s a good platform. And I joined the Worldwide Speakers Group, so I do a little speaking.

Frank, tell us about the mission of the Dirksen Center and how Ray LaHood fits into that mission.

Mackaman: Our mission is to help the public better understand Congress, the people who serve there, the processes and procedures involved, and the public policy it produces. We have uninterrupted, continuous coverage of this district from 1933 to present. So Ray’s career and his collection offer a lens through which to view Congress.

What makes the Dirksen Center unique?

Mackaman: The Dirksen Center is a charter member of the Association of Centers for the Study of Congress. There are about 45 members, and many other congressional repositories, but we are, to my knowledge, the only free-standing, independent institution. We don’t have a parent—whether a college or university, state historical society, or state records agency. We are also unique in our comprehensive coverage of a single congressional district, and we are the only congressional repository with a grant program that funds basic research about Congress without requiring the research to be done at a particular repository. This year, we will pass on over a million dollars… never giving more than $3,500 away at a single time. That’s nearly 500 individual research projects.

How did the Center get its start?

Mackaman: We received our state charter in 1963, and nothing happened. Conventional wisdom is that Everett Dirksen did not want people raising money to fund its establishment while he was still in office. But he dies in office in 1969, and immediately, the ability to raise money for the Dirksen Center evaporates with his death.

In the early 1970s, a group of Pekin community leaders joined with his former aide, Harold Rainville of Chicago, and started raising money for the Dirksen Center. Pekin Public Library decides they need to expand, [but] they need a partner… so this group joins with the library board, and they raise the money to pay for the building. Ground is broken in 1973; the building is dedicated in ‘75. When I come on board in 1976, there were no shelves—all of Dirksen’s collection is sitting in boxes on the floor. I think the endowment fund was $110,000.

Our big break came in 1978 when [Sen.] Hubert Humphrey died and Congress introduced legislation to earmark $5 million for the Hubert Humphrey School of Public Affairs at the University of Minnesota. Then, Bob Michel on the House side and Howard Baker on the Senate side attached an amendment… to get $2.5 million for the Dirksen Center. God bless Bob Michel! The story is that when asked why Humphrey got $5 million and Dirksen got $2.5 million, Bob replied, “Everett always claimed he could do the same thing Hubert could for half the money” (laughs). So that was, in essence, an endowment grant.

When Bob retired, he was honored with an appropriation from Congress that took an unusual shape: a $5-million line of credit administered by the National Historical Publications and Records Commission. That had the effect of leaving this $2.5 million untouched. So at the end of that grant, our endowment fund had climbed to over $5 million. We are now living on the proceeds of the endowment fund investment; we don’t do fundraising. Scattered throughout this time, there are some big grants, including a six-figure grant from the Ford Foundation.

How do you view former Rep. Aaron Schock, vis-à-vis the legacy of the district? Are you interested in pursuing his papers?

How do you view former Rep. Aaron Schock, vis-à-vis the legacy of the district? Are you interested in pursuing his papers?

Mackaman: I’m not going to rush to judgment, so I don’t have a conclusion about the general question. Are we interested in his papers? Yes.

And now Darin LaHood represents the district. How soon do the wheels start turning in terms of making arrangements to obtain his papers?

Mackaman: I sent his chief of staff a letter [in November] explaining what the Dirksen Center is, and enclosed a records manual, which contains recommendations about what to save, for how long, and the ultimate disposition of the collection. I welcome a chance to sit down with them to express our interest in the collection. It is unusual for a member of Congress to designate a repository early in his or her term, so this is a game with a long horizon.

Do these collections include digital files as well as physical papers?

Mackaman: Yes. Ray’s papers actually presented us with the first challenge on the digital front. [Former District Chief of Staff] Tim Butler—his speech files and appointments were all digital, so we started to face that with Ray’s collection, and we’ll face it with much greater volume and complexity with Darin’s papers. We are also interested in documenting the use of social media, as well as the traditional things you expect to see, regardless of format. One of the things we did with Dirksen and Michel—which we won’t do any longer, except on a very limited scale—is accept three-dimensional items. We have a pretty rich collection in Dirksen and Michel’s cases, [but] they don’t really support our mission very effectively for the cost of preserving them.

You also have Rep. Harold Velde’s papers…

Mackaman: Harold Velde is unusual because when the Republicans had the majority in the House following the ’52 election, he chaired the House Un-American Activities Committee, and was chairman during the Hollywood trials. His papers were preserved by a private party in Morton for a long time. Unfortunately, they were stored in a basement that flooded, so by the time we got the collection, it was a remnant, but there are some good pieces in that collection.

Who comes to the Dirksen Center to review such material?

Mackaman: Because we have digitized so much material and posted it on the Internet, we have no way of really tracking use. We have website statistics, but that doesn’t tell you how people use the collection. In terms of folks who actually visit us, it’s very few. Almost all of the reference work we do is done remotely. Our finding aids are online, so someone will say they want to see these three folders; depending on what’s in the folders and the time involved, we’ll digitize them and send them as PDF files, and they never need to come here.

Do you view yourself as a caretaker of the district’s history?

Mackaman: I don’t see myself as a caretaker; I don’t even consider myself a historian in the traditional sense. I try to figure out how to take the content in our collections and leverage it, either by creating educational programs, or making the materials themselves more available. I don’t do much interpreting of history. When I write about the Civil Rights Act of 1964, for example, I’m not doing it to make a mark in the field of academic history. I’m not trying to come up with novel interpretations. I think the value of history is the way it teaches a person to think. The value I get from my historical training is not that I know what happened in 1932—it’s how I approach problem-solving and thinking.

You used to be director of the Gerald R. Ford Library and Museum. How did you land that position, and how has it informed your work here?

Mackaman: I got the job because of my work at the Dirksen Center. I came here in 1976, left in 1987 to work for President Ford, and came back in 1996. I got the job as deputy director in 1987 because the director, Don Wilson, did consulting at the Dirksen Center and learned what we were doing. Somehow or another, President Ford found out and asked him to ask me if I would join the Ford operation. For a variety of reasons, I said yes. A year and a half later, Don Wilson got the job as Archivist of the United States, which created a vacancy in the director position, and I was promoted to that. It was very interesting because I start out at a small nonprofit working on Congress, and move to a large federal bureaucracy, working on the presidency. The combination of the two has been a marvelous experience. That I’ve worked with two of the three branches of government has helped me understand each better than if I had studied one of them singularly.

Having spent so much time with the collections here, are there still parts that even you haven’t uncovered yet?

Mackaman: I could work here for a long time. We have these congressional papers, and we have about 150 other collections... For example, we have the papers of Neil MacNeil—pound for pound, probably our best collection. He was a Capitol Hill correspondent for Time magazine for 30 years, from the late ‘50s to the mid-‘80s… His papers contain his reporting to his editors in New York about what was happening in Congress. This is off-the-record, unedited stuff—the raw material he is shipping for Time magazine cover stories… The project I am working on now is to reproduce all of his reporting on Everett Dirksen. He also reports on Bob Michel for a period of time, so that will be next. There are opportunities like that in all of the collections.

Is there anything else we didn’t discuss that you would like to talk about?

LaHood: Something that fascinated me, which Frank didn’t mention, a guy named Todd Purdum… He wrote a book on the 150th anniversary of the civil rights bill. He spent a week here, and I found that fascinating because that is sort of how I think in terms of my book. Twenty-five or 50 years from now, if one of my grandkids wonders why their grandfather made the decisions he did, there is a document they can look at. People can’t just sit around and speculate about my career anymore; it’s all documented. Purdum came here to figure out why Dirksen did certain things. I think that’s the value of a place like this.

So you can just say, “Read the book!”

LaHood: Exactly. People will say, “Why didn’t you sign the Contract with America?”—there it is. The other thing is the uniqueness of this district—it’s just extraordinary. I don’t think there is another place like it in the country. iBi

For more information on the Dirksen Congressional Center, visit dirksencenter.org. Seeking Bipartisanship: My Life in Politics, by Ray LaHood with Frank H. Mackaman, is available at amazon.com and from booksellers nationwide.