To Burma and Back

Nearly 70 years after the end of World War II, the legacy of Little Peoria’s big impact in the China-Burma-India Theater lives on.

“Today you are setting forth on a journey of great importance. You do not know your destination. You do not know how long you will be gone. But you do know that it is your high purpose to serve your country in this time of its greatest need. And you do know—and I know—that you will steadfastly devote yourselves to that purpose until victory is won.”

When former Caterpillar Tractor Co. President L.B. Neumiller spoke those words from the steps of the Peoria County Courthouse on October 1, 1942, he was delivering a farewell speech to nearly 200 brave men about to embark on a journey halfway around the world. They would leave behind their loved ones and the quiet comforts of the Midwest to descend into the depths of the Burmese jungle during the thick of World War II. They were the men of Caterpillar’s own 497th Engineer Heavy Shop Company.

Conflict in the East

Before the world’s great military powers were pulled into a second global war that would last a grueling and deadly six years, conflict was already brewing in East Asia. In the summer of 1937, eager to expand their influence in the Pacific, Japanese forces invaded China and seized its eastern seaports, initiating the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War. With their waterways under siege, the Chinese sought a new supply line to receive vital war goods and found their solution in constructing the Burma Road, a land route stretching more than 700 miles from eastern Burma to southern China. However, in the spring of 1942, Japan seized control of Burma and closed the road at its source, isolating China from its allies as World War II raged on.

With its harbors and principal land route shut down and Japanese fighter pilots making airlifts increasingly dangerous, China looked to its border with India to establish a new ground transport line. There, however, loomed the mighty Himalayas, separating the desperate nation from the resources it needed to fight further advances by the Axis powers. With the freedom of millions on the line, Allied forces, including thousands of American troops equipped with Caterpillar machinery, began what Brigadier General Lewis A. Pick described as “the toughest job ever given to the U.S. Army Engineers in wartime”—the construction of the Ledo Road.

A Call to Caterpillar Men

Entwined in the war effort even before the attack on Pearl Harbor, the bulk of Caterpillar’s equipment was already being sent to the Allies for military construction and defense use before the Burma Road was shut down. But when it came to building the Ledo Road, the dependence on Cat machinery was greater than ever. In order to create the 478-mile route, which would link the railhead of Ledo in the far north of India’s eastern arm to a junction with the old Burma Road near the China-Burma border, a bevy of bulldozers and tractors was required to clear a path through the region’s swampy valleys and dense, mountainous jungles.

In need of skilled workers to maintain and repair the equipment being used in India and Burma, in July of 1942, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers called on Caterpillar to form the 497th Engineer Heavy Shop Company. The brainchild of Lt. Col. C. Rodney Smith and Caterpillar Assistant Service Manager Ralph G. Dunn, it was the first unit in American history organized by a manufacturing company and manned primarily by its own employees. “Think what that will mean to each man in the outfit. Think how it will set this Heavy Shop Company apart from all others,” read one recruitment pamphlet. “Think of what it will mean to every ‘Caterpillar’ man who joins up with other ‘Caterpillar’ men in the first company of its kind… It will be your Company, our Company, from top to bottom.”

That September, 191 men—158 Caterpillar employees and 33 other locals, who worked as blacksmiths, carpenters, electricians, foundry men, machinists, mechanics, welders and more—were sworn in at the recruiting office on Main Street, ready to be activated on October 1st. Ralph Northrup, then a 21-year-old farmer from Trivoli, was one of those men.

Shortly after receiving his draft notice, Northrup, better known as “Northy” by his companions, enlisted with the 497th as a mechanic, hoping to be shipped overseas with other local men, rather than complete strangers. “I’d never been away from home, to tell you the truth, to stay overnight,” he chuckles, recalling the apprehension he felt before setting off to a then-unknown destination.

On the morning of their departure, the new G.I.s, led by Captain Jean Walker, assembled at the Peoria County Courthouse for a grand sendoff ceremony before marching down to the Rock Island Depot. There, Northrup and the others waved goodbye to their loved ones and began their long, tumultuous journey to Shingbwiyang, Burma.

Journey to the Jungle

Following a brief stop in Scottsfield, Illinois, where they were outfitted with uniforms and equipment, the 497th traveled to Camp Claiborne in Rapides Parish, Louisiana, where the men got their first taste of military life. After enduring basic training, the company spent several months at another military camp in California before boarding a train to Camp Patrick Henry in Warwick County, Virginia, where the 497th set out to sea as part of a large convoy headed to North Africa in September of 1943.

After a few miserable weeks in Algeria, where they slept on hills of rocks, exposed to the cold, damp fall air, the men prepared to board the HMT Rohna, a stately British troopship headed for Bombay, India. “Everybody… thought they were going to get up on this big ship,” Northrup remembers. “They floated us out to it, and a few of us got on it. Then they told us to get back off—it was full. So we were kind of disappointed.”

After a few miserable weeks in Algeria, where they slept on hills of rocks, exposed to the cold, damp fall air, the men prepared to board the HMT Rohna, a stately British troopship headed for Bombay, India. “Everybody… thought they were going to get up on this big ship,” Northrup remembers. “They floated us out to it, and a few of us got on it. Then they told us to get back off—it was full. So we were kind of disappointed.”

Instead, members of the 497th boarded a small British coal burner, the Agra. “The food was hardly fit to eat on that old ship—cockroaches in the oatmeal and stuff,” Northrup remarks. “And it was very crude accommodations. They put us down in the hole there—12 men at a table… You either slept in the hammock or under the table, wherever you could find a place to lay.” Despite their cramped quarters, not a single one of the men wasn’t thankful to have been aboard the Agra on November 26, 1943—the day their convoy came under attack.

“I was down in that hole, and the alarm went off. There were airplanes coming; we were being attacked,” Northrup recounts. “These German bombers were up there pulling two glider bombs—little [remote-controlled] airplanes behind them… This one big bomb, we saw it sail in and hit this big British ship.” That ship was the HMT Rohna, which sank to the bottom of the sea, taking more than 1,100 men down with it. To this day, the attack constitutes the largest loss of American troops at sea in a single incident.

When the battle with the German Luftwaffe was over, the convoy trudged on through the Suez Canal and across the Arabian Sea, finally docking in Bombay in late December. From there, the 497th embarked on the next arduous leg of its trip, traversing India by train to Kanchrapara, a city just north of Calcutta near India’s northeast coastline. The ride was long and marked by hunger, Northrup recalls. Besides their limited amount of “C” rations (canned, pre-cooked and prepared wet foods), the men subsisted on the bananas and boiled duck eggs they bought from local vendors along the way. Northrup distinctly remembers his Christmas dinner on that train, consisting of just a jelly sandwich and a cup of tea. After ringing in the New Year in a staging camp at Kanchrapara, the company crossed the border into Burma to begin a laborious 20 months of service on the Ledo Road.

Little Peoria Around the World

Wiggling through the mountains of northern Burma, the Ledo Road passes through some of the world’s toughest terrain. Not only were the soldiers subjected to unrelenting tropical heat and the torrential downpours of monsoon season, but other dangers lurked in its jungles, from wild hogs and tigers to typhus and malaria.

The 497th ended up settling at the 103-mile mark on the road in Shingbwiyang, where construction had progressed by the beginning of 1944. Atop a hillside surrounded by rainforest and wildlife, the men christened their camp “Little Peoria.” It served as both living quarters and as a maintenance station for the Caterpillar D7 and D8 bulldozers, motor graders and other equipment being used to excavate the rocky landscape and install miles of telephone and fuel lines along the length of the new route.

Life at Little Peoria was tough. Furnished with cotton tents designed for desert use and work shelters fashioned out of canvas and bamboo, Northrup remembers the camp as “awful muddy and wet.” “When the monsoon [started], your bed was always moldy or damp,” he notes. “You had a time getting anything dry.” Fresh food was scarce; a typical meal consisted of corned beef and canned green beans or other British-distributed rations, unless someone had been out hunting and was lucky enough to get a deer. Once a month, the company received a PX ration, usually consisting of a carton of cigarettes, a roll of Necco Wafers, a tin of Whitman’s chocolates, some fruit juice and a case of beer.

Not only soaked and hungry, the company also had its share of close calls. Despite receiving a daily dose of Atabrine—an anti-malarial tablet that, as Northrup recalls, turned their skin yellow—several men contracted malaria, landing them in a makeshift, dirt-floor military hospital nearby. And though the 497th was not a combat unit, the warfront was never far away. “We could hear the gunfire and the fighting,” Northrup remembers. In addition to frequent dogfights over the camp as American pilots attempted to fly over “the Hump” (the Himalayas) into China, Japanese forces once managed to cut off a portion of the Ledo Road behind them, causing a panic amongst the men. “We got ready. We thought we were going to be called out to help fight the Japanese.” But before being called to the frontlines, Chinese and Indian forces, alongside the U.S. special operations unit known as Merrill’s Marauders, drove the invaders back out of Burma.

But life wasn’t all bad at camp, and the men found ways to entertain themselves and enjoy some of the comforts of home. They erected three metal buildings to house their machine, carpenter and electric, and welding shops, kept running by three diesel generators that also provided electricity to their tents, mess hall, shower room and kitchen. Several of the men used their trade skills to rig up can openers, potato peelers, furniture or anything else that was needed. “We had some wonderful boys in our section,” Northrup declares. “I was in repairs, in the third platoon. We had a machine shop where they could weld and stuff. They could make pretty much anything.” One of the most appreciated homemade inventions they produced: the beer cooler. “We got a case of beer a month, but of course, we had no way of cooling it… We had air compressors, so we’d take a can of gasoline and put a beer in [it], and the evaporation would cool that beer. That’s the way they cooled the water, too.”

Though now deceased, Terence Whitsitt, another member of the third platoon, reminisced about the company’s adventures in his memoir, History of the 497th Engineers. “One of our amenities was the best whiskey still in Burma,” he wrote. “One of the guys from Oklahoma was a skilled moonshiner. He set up the still up along a little stream nearby. The other guys working in twos put the mash together and took their turn at running it off. When they finished a batch, they took it to a headman and he colored it and sold it. However, the legal arm of the army got noisy and we had to give up the project.”

Another innovator among the men, Whitsitt said, was Clyde Robins. “He fixed up his tent like no one else. He mounted a fan from a truck on an electric motor and mounted it in a hole cut in the center of the floor. He also obtained some large boxes about three feet by six feet, stood them on end and installed a micro switch in each one. This made a nice clothes closet. He put eaves troughs on one side of the tent and collected water, ran it through an electric heater, and had hot and cold running water.”

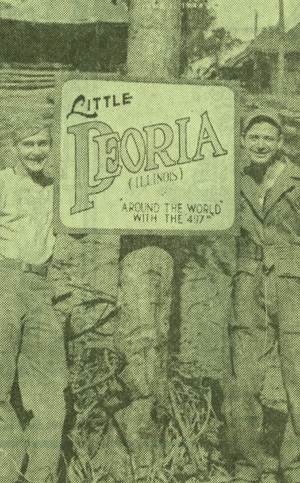

Bringing memories of home with them, the men named the paths, tents and shops of their camp after prominent Peoria roadways and institutions. Hammered to a tree in the middle of the jungle, a homemade marker declared the base “Little Peoria (Illinois)—Around the World,” and company carpenters fabricated signs reading “Hamilton Blvd.,” “Monroe St.,” “Buehler Home,” “Sheridan Inn,” “Faust Club,” “Gipps” and more—all small reminders of what waited for them thousands of miles away. Northup also remembers enjoying movies on the hillside, catching some of the biggest fish he’s seen in his life out of the Burmese rivers, exploring India while on “R&R,” and forging lifelong friendships with many of the men he worked with, day in and day out, for more than three years. “They were really good people and would do anything for you,” he proclaims. “We’d help one another.”

A Lasting Legacy

Just as the men relied upon one another in times of hardship, they also came together to relish their victories. Around the first anniversary of their arrival at Shingbwiyang, engineers completed the Ledo Road, renaming it Stilwell Road in honor of General Joseph “Vinegar Joe” Stilwell, commander of the China-Burma-India Theater. In January of 1945, Brigadier General Lewis A. Pick led the first convoy out of Ledo and successfully traversed the Burmese border. Their arrival in China was the culmination of more than 15,000 troops having moved 13.5 million cubic yards of earth, digging more than 1.38 million cubic yards of gravel, and building more than 700 bridges across 1,079 miles. In the months between its opening and the Japanese surrender, the road allowed the transport of some 129,000 tons of supplies, 26,000 vehicles, 6,500 trailers and more than six million gallons of fuel from India to China.

As the war wound down, in the late summer of 1945, the 497th transferred to a debarkation camp in Karachi, India, and soon after, set sail for the states. After withstanding weeks of rough seas and anxious anticipation, and enduring one last train ride to Camp Grant, near Rockford, Illinois, the company was finally discharged—just in time for the holidays—on December 10, 1945.

Bonded by their shared experiences, the men established a club, the 497th Engineers Incorporated, to keep in touch after the war’s end. After purchasing a clubhouse in Groveland, members of the 497th and their families for years met regularly for pool parties, corn boils and clam bakes—and just to reminiscence about their time in Burma. But as time went by, the number of clubhouse meetings dwindled, as did the company’s members, until they decided to sell the building. In 2002, the remaining 497th “Fighting Engineers” came together for one final celebration—the 60th anniversary of their departure for the Ledo Road.

Today, though all but a few of its members have passed away, the legacy of the 497th lives on—through the stories passed down to loved ones; the diaries and mementos they kept; and the freedom we enjoy to this day because of their efforts—and those of countless others—during World War II. While Northrup cherishes his collection of newspaper clippings, black-and-white photographs, and the ribbons and bronze battle star he earned during his tour of duty, his memories of Burma and the voyage there and back are as vibrant as if it all happened yesterday. He still hears the monkeys chattering in the trees. He can still smell the distinct aroma of burning cow patties wafting from the Indian villages. He still sees the glowing eyes of the jackals watching over camp. And he still feels the comfort of knowing, with every bone in his body, that there’s no place like home. “Sometimes I lay in my bed at night before I go to sleep, and I’ll go over that stuff through my mind… I’m never going to forget any of it as long as I’m living. I know that.” iBi